DIA

s increased diversity of patient populations who participate in clinical trials becomes more entrenched as a modern business, clinical, and regulatory requirement, new trial technologies and tools continue to emerge to help research and researchers meet these obligations. The combined impact of all these forces (see sidebox) is helping to focus research on more specific patient populations and needs. But this impact has built up enormous complexity for clinical trial data management and analysis.

From a scientific perspective, the only way that all communities will benefit from clinical research is for that research to study a therapy’s impact on people from all communities: people in various living conditions, and of different ethnicity, age, and other characteristics.

Analysis of 2020 US population and FDA drug approval statistics illustrates the problematic disconnect between clinical research participants and real-world populations in the US. In the 2020 census, the US population was 12% Black/African-American, 19% Hispanic/Latin American, and 58% White. But participants in the clinical trials supporting the 53 novel drugs the agency approved in 2020 were 8% Black/African-American, 11% Hispanic, and 75% White. (The Asian population was 6% across both metrics.) These differences illustrate unequal opportunity and potentially inaccurate science.

From the legislative and regulatory perspectives, the US Congress in December 2022 passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, including the Diverse and Equitable Participation in Clinical Trials (DEPICT) Act and the Diversifying Investigations Via Equitable Research Studies for Everyone (DIVERSE) Trials Act, both aimed at increasing the demographic diversity of participants in clinical trials. (DIVERSE also addresses social determinants of health.) Earlier in 2022, the US FDA had issued guidance on preparing Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants From Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials. Compliance with these requirements and guidelines also requires researchers to know more demographic details to identify these subgroups.

Clinical Trial Data Analysis Can Help: Future State

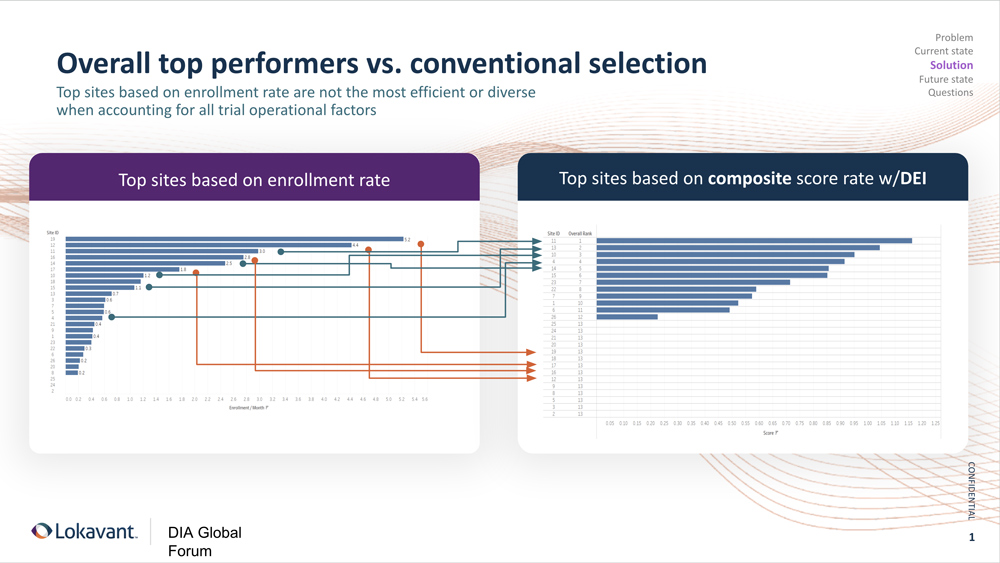

The below slide incorporates data gathered from study sites in the US and analyzed by a technology vendor for a global CRO. These sites had conducted two or more trials in the US and were selected from this vendor’s proprietary data set of more than 99,000 study sites. Site selection was therapeutic area agnostic.

The vendor then modeled the projected performance of each site based on historical clinical trial data for these sites and investigators: Not just how quickly they enrolled participants but quality measures such as how well they maintained the participants’ treatment regimen and safety and adhered to the study protocol. This first analysis, on the left side of the slide, indicates that the top five performing sites would be sites 19, 12, 11, 16, and 14.

But meeting these new requirements, by answering how many of which type, requires deeper insight into data about the participants, not just the sites. In this example, different real-world healthcare data sources were linked to participants by deidentified tokens representing their demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic circumstances. Zip codes, for example, are widely considered predictive of future health needs in economically disadvantaged rural and urban settings.

This refined approach culminates in looking at more than just enrollment rate but also at which sites are the best for meeting the diversity goals of the study–a tool that gives study site staff the ability to self-monitor, in real time, and “course correct” if necessary to make sure they’re achieving both the enrollment goals and the diversity goals. This requires several enabling technologies: Data must be harmonized across the entire study, and then localized to each specific site. Study site staff must have specific permissions to monitor their daily recruitment, enrollment, and randomization numbers at a deeper demographic level.

“As we identify investigators that traditionally haven’t been included because we’re moving away from only using preferred sites, I think industry will find a number of physicians (not investigators) without investigator experience. These physicians have participants that are diverse and of interest for a given trial, but we need to support that position by training them to be a clinical trial investigator, because it’s not an easy step,” suggests Lokavant CEO and founder Rohit Nambisan.

In this example, a predictive analytical model that incorporates these demographic data projects that the top five performing sites—the sites that will achieve not only the enrollment but the diversity goals—will be sites 11, 13, 10, 4, and 14 (which came in fifth in both analyses).

“The other area we can improve is on the participant side. There’s just not enough information out there that can be consumed,” Nambisan concludes. “If we want diverse participation, information needs to be provided in languages that are diverse, too. There’s just not enough knowledge and access to the patient populations that are being disproportionately affected by these conditions. That’s the short-term opportunity available to us as a global clinical research powerhouse.”

Goals for enrollment of underrepresented racial and ethnic participants: Specify goals for enrollment of underrepresented racial and ethnic participants (e.g., based on the epidemiology of the disease and/or based on a priori information that may impact outcomes across racial and ethnic groups; and where appropriate, leverage pooled data sources or use demographic data in general population). In some cases, increased (i.e., greater than proportional) enrollment of certain populations may be needed to elucidate potential important differences.

Specific plan of action to enroll and retain diverse participants:

- Describe specific trial enrollment and retention strategies, including but not limited to site location and access (e.g., language assistance for persons with limited English proficiency, reasonable modifications for persons with disabilities, and other issues such as transportation); sustained community engagement (e.g., community advisory boards and navigators, community health workers, patient advocacy groups, local healthcare providers, etc.); and reducing burdens due to trial/study design/conduct (e.g., number/frequency of study-related procedures, use of local laboratory/imaging, telehealth).

- Describe metrics to ensure that diverse participant enrollment goals are achieved and specify actions to be implemented during the conduct of the trial(s) or studies if planned enrollment goals are not met.

Status of meeting enrollment goals: As the diversity plan is updated (when applicable), discuss the status of meeting enrollment goals. If the sponsor is not able to achieve enrollment goals despite best efforts, discuss a plan and justification for collecting data in the post-marketing setting.