How China is Changing the Clinical Development Landscape

Implications for Global Development Strategy

dMed Biopharmaceutical

dMed Biopharmaceutical

n less than 24 months, China has radically altered the global clinical development landscape, creating new pathways to commercialization that alter the traditional drug development paradigm.

In addition to making the world’s second largest market more accessible virtually overnight, the more profound impact on the industry is the way in which China’s policy revamp and emerging global role point to a new and exciting paradigm for future global clinical development and regulatory strategies.

Previous 20th Century Drug Innovation Model

- strong public sector funding of US academic research;

- FDA’s role as the global gold standard for regulatory approval;

- availability of capital from both public markets and venture capitalists (VCs); and

- high US drug prices that incentivized companies and investors to focus on US-centric drug development.

Each driver of US pre-eminence has steadily undergone gradual erosion. Stagnant public sector US research funding, globalization of development and regulatory guidelines, diversification of global capital sources, and growing US domestic political pressure to end the US price subsidy for global drug innovation, have become familiar themes.

With 60 to 70 percent of drug development cost coming at the clinical stage, an increasingly important nail in the coffin of the old model lies in the competition for trial subjects in the US. Streamlined regulations and deployment of new technologies have not changed the fundamental math of clinical development: Today, too many US trials chase too few subjects. This challenge will continue to grow as precision medicine calls for more specific and exclusive inclusion criteria. The inevitable result: slower recruitment, longer trials, and rising direct and indirect costs that, in turn, must be shared across a more narrowly defined base of potential US patients willing or able to pay higher prices.

Drivers of the Emerging Drug Innovation Model

For example, Chinese approval for clinical trials that previously would have taken years now take 60 working days, making it possible to include China in global phase 2 and phase 3 trials. Moreover, US regulators will accept Chinese data, if it meets global quality standards. We increasingly pursue simultaneous pre-IND meetings with both the US FDA and China NMPA to ensure full alignment of the clinical plan across the two leading markets.

Another example is patient recruitment speed. In areas where US trials struggle to recruit patients, including immuno-oncology, NASH, chronic diseases, and a host of orphan indications, China has a wealth of treatment-naive patients concentrated in top urban medical centers with direct costs generally 30 percent lower than in the US. As a result, recruitment could often be 2-3 times faster. Additionally, using a small handful of sites makes project management and quality assurance simpler while developing deeper relationships with internationally recognized principal investigators (PIs).

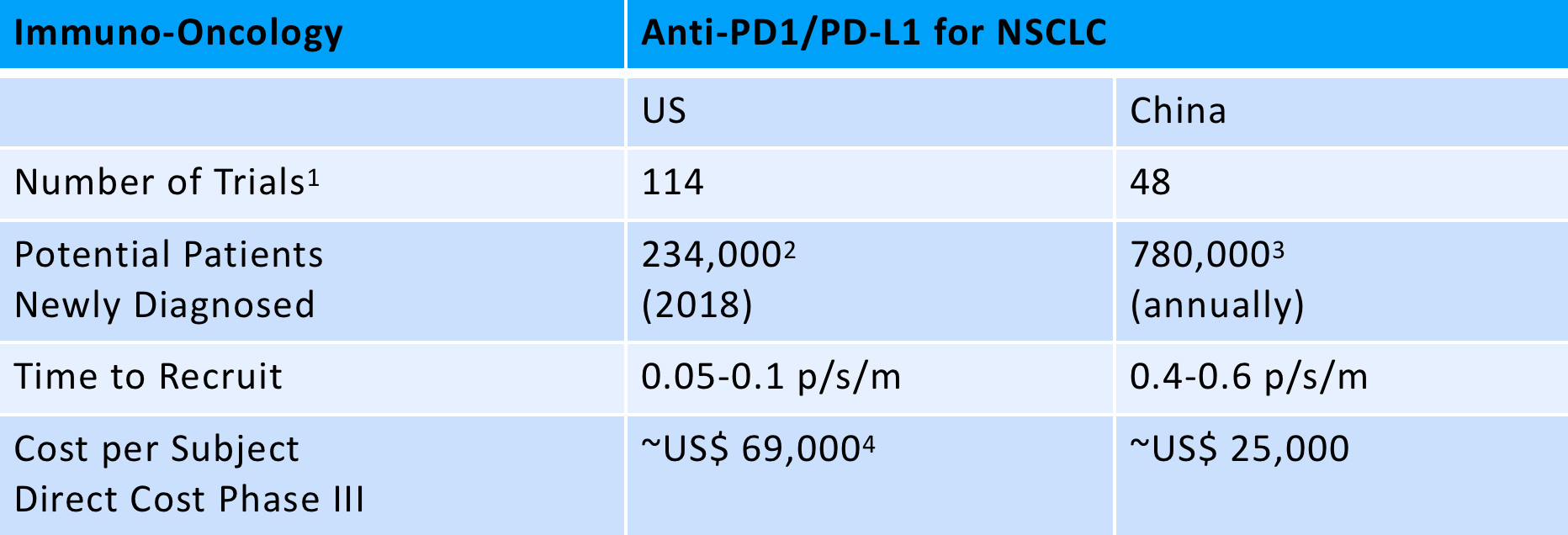

As an example, the below table shows the number of trials for PD-1/PDL-1s in non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) patients and the number of newly diagnosed patients annually in both the US and China. Not surprisingly, the speed of patient recruitment and direct costs look more attractive in China. The gap is narrowing as both innovative Chinese firms and more globally-attuned Western biotechnology companies begin to leverage China’s attractions, but the potential impact on the time and cost of trials offers a compelling reason to rethink the balance of sites between the US/EU and China.

- Clinicaltrial.gov Trial started: 01/01/2013 – 01/04/2019

- https://cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- https://gbtimes.com/lung-cancer-tops-chinas-malignant-tumour-incidence-rate

- PhRMA: Biopharmaceuticalceutical Industry-Sponsored Clinical Trials: Impact on State Economies, 2015)

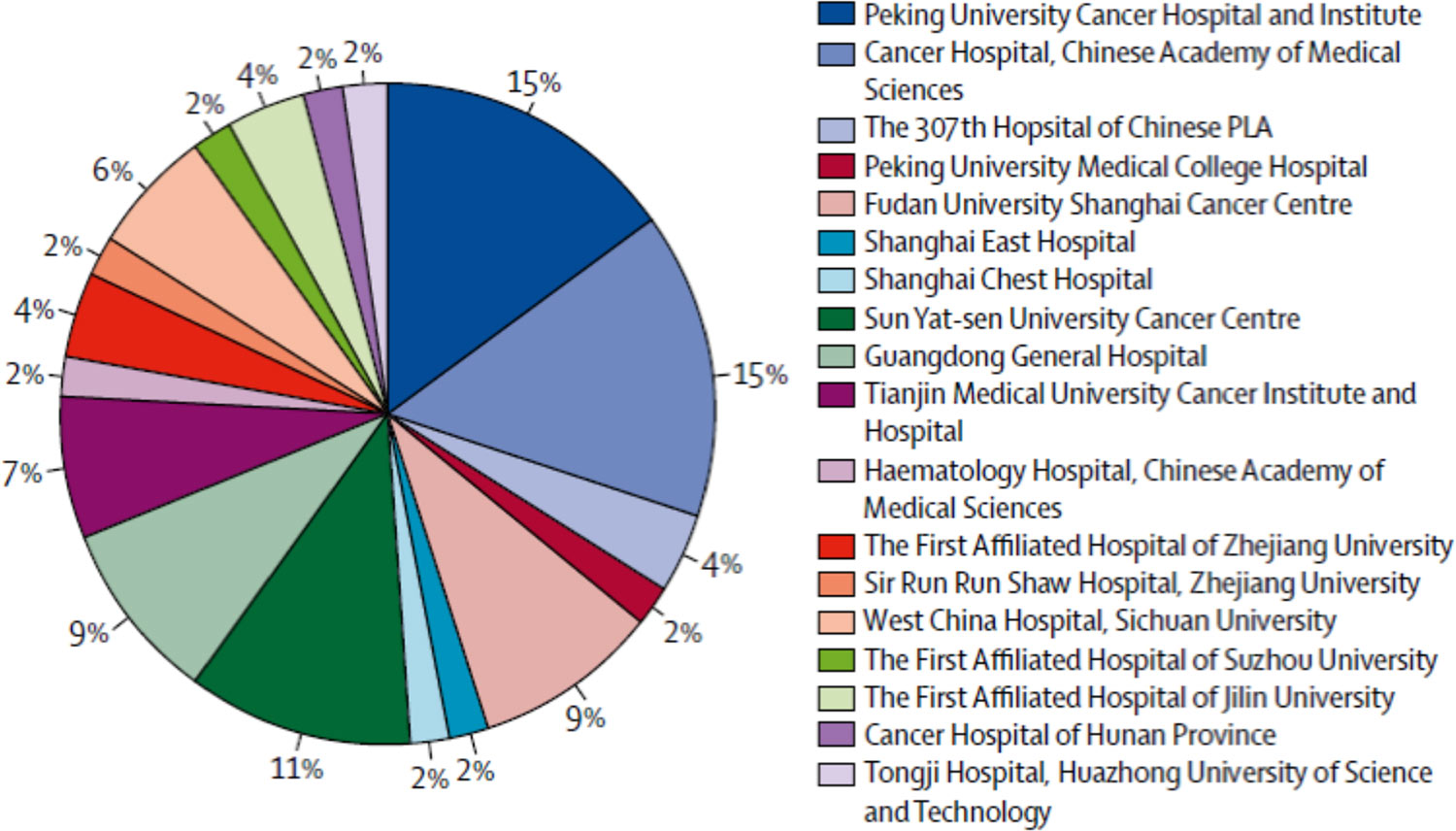

The below pie chart shows the distribution of clinical trial sites for 180 oncology studies conducted in China. Nearly 60 percent of these studies are concentrated in just five sites; dozens of high-quality sites have yet to be fully utilized.

For an added incentive, innovative drugs–mainly from foreign firms–are being added to the National Reimbursed Drug List (NRDL) for the first time, albeit at steep discounts. The first 30 drugs (mainly oncology treatments already available in China) entered national reimbursement in 2017 with price cuts ranging from 50 to 70 percent. Roche, the firm with the largest number of newly listed therapies, saw demand for its drugs grow dramatically, with volume more than making up the difference in top-line sales and profitability. In 2018, 36 innovative drugs were added to the NRDL. A fresh batch of innovative drugs is likely to be announced in the third quarter of 2019.

Mapping the Future

- Simultaneous pre-IND meetings with both the FDA and China NMPA in order to design a clinical and regulatory strategy that works across both markets.

- Initiate trials in both countries, with the distribution of subjects designed to maximize speed and reduce cost while delivering the data needed by the US, Chinese, and other key regulators.

The Critical Challenge

Questions most frequently asked by Western companies include:

- How do I navigate the Chinese landscape with its myriad of different commercial partners, CROs, and investors?

- Where are the resources to bridge our lack of understanding of the clinical development terrain and regulatory nuances? Won’t these generate huge potential management distractions?

- Can I be sure that the quality of data from China will support my global program and meet key milestones?

Definitive answers clearly depend on the specifics of each company’s capabilities and goals. However, here are a few practical suggestions that may be useful:

Look to partners with deep experience developing innovative drugs in China.

Only a handful of long-established Chinese biopharmaceutical companies have either clinical or regulatory experience beyond their generic product portfolios. Innovative Chinese biotechnology companies are more attuned to the complexity of innovative medicines, but only a select few have moved the bulk of their assets from the lab to the clinic. Additionally, most CROs–local and global–have built organizations designed to meet the needs of China’s former model, focused on gaining approval for local generics or innovative Western drugs already registered for years in the US and Europe.

Find a team you can trust to collaborate smoothly and effectively with your global clinical and regulatory professionals.

Besides overcoming obvious challenges such as language and differences in clinical practice, at the heart of this challenge lies your China partner’s understanding of and commitment to global standards. This capability generally can only be found among teams with decades of experience in managing clinical development on the ground in China for leading global biopharmaceutical companies.

Structure the approach and timing to maximize value.

While transactions for China rights have been rising in value, Chinese investors and licensees drive hard bargains and demand extensive data to support attractive valuations. Consequently, upfront investment in early clinical development while advancing Chinese registration can pay a high dividend, whether seeking to partner China rights locally or building toward a global transaction. Bridging the financial gap to make that upfront investment has become increasingly easy to achieve.

Seek a shared “owner’s mindset” by asking yourself:

- Does the commercial partner share your passion for the molecule and its global development, or are they narrowly focused on local commercialization and clinical support for local regulatory approval?

- Does your CRO’s China team see themselves as a service provider that dutifully checks the boxes, or do they act like true partners who help anticipate challenges and offer innovative solutions that reflect both China’s complexities and those of your global development objectives?

As food for thought, I end with a question that seasoned CEOs of leading US VCs often ask: For our potential investment candidates, are they open to leveraging the new global development paradigm, or are they entrenched in the past, destined to “wait and see” while others leap ahead? How you answer and act upon this question can make all the difference.