Ethical Considerations on Clinical Trial Participation and Management in Wartime Conditions

Perspective from the IFAPP Ethics Working Group

o draw conclusions from the war in Ukraine which might be used in other catastrophic situations, we must evaluate events and facts carefully and objectively. It is useful to refer to the original concept of the Red Cross movement, which states that victims of war should be protected irrespective of which warring party they belong to. We should be guided by the principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence, and universality.

In April 2022, very early in this war, the Ethics Working Group of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Physicians and Pharmaceutical Medicine (IFAPP) published a statement and conclusions concerning research ethics and good clinical practice (GCP) in the unfolding war in Ukraine. We concluded that there might be vulnerable populations in both Ukraine and Russia since the armed conflict was very rapidly followed by severe economic sanctions against Russia. As a result, we face two parallel wars: an armed conflict and an economic conflict.

This conclusion led us to study the effect of these types of wars on participants in clinical trials. Russia’s military confrontation with Ukraine has already resulted in an enormous number of human casualties including civilians, research personnel, and research participants. It has also destroyed many healthcare facilities and profoundly disrupted the social infrastructure of Ukraine. The war is creating major problems for clinical trials in Ukraine in such areas as trial participant access to the investigational treatment, performing laboratory tests, and sending documents and biological samples to various facilities.

What is happening in Russia as a result of economic sanctions? Many Western pharmaceutical companies suspended drug development programs and paused communications and contacts in Russia. Sponsors stopped patient accrual into ongoing trials almost immediately. Provision of trial medicines stopped, and sending documents and biological samples abroad was interrupted because commercial air traffic into and out of Russia ceased. There were no direct human casualties. The healthcare infrastructure in Russia remained intact.

Our ethics working group subsequently published the short communication The Ethical Responsibility to Continue Investigational Treatments of Research Participants in Situation of Armed Conflicts, Economic Sanctions, or Natural Catastrophes. We concluded that there are three phases of such catastrophes.

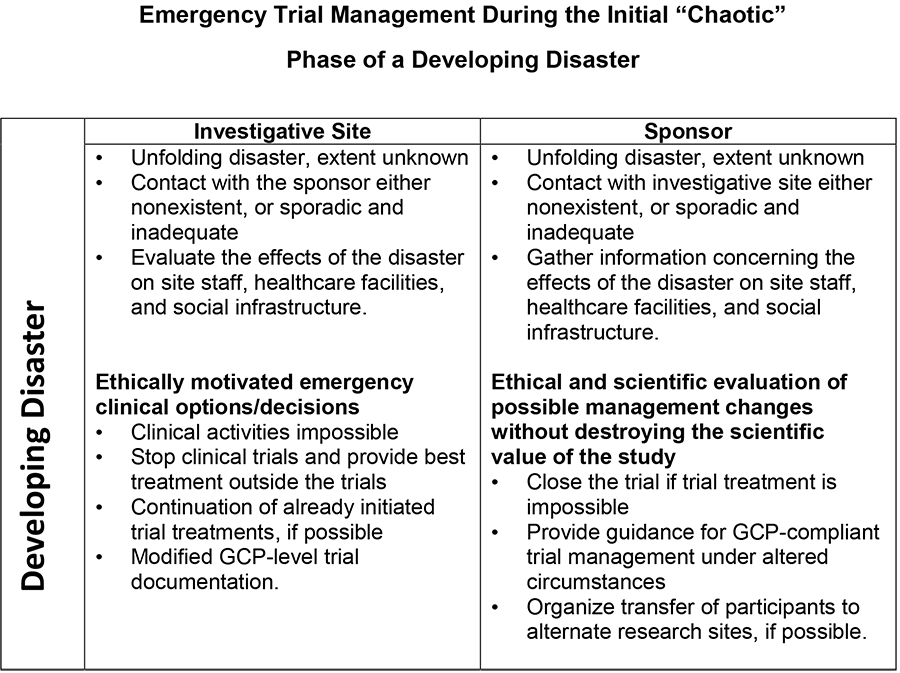

- First, a “chaotic phase.” As the situation is developing, the response takes the form of emergency trial management.

- If the catastrophe is prolonged (like this war), then a functional trial management system can be fit to the changed circumstances.

- At the conflict’s end, a vast consolidation phase will secure return to normal trial management. Unfortunately, this process might take quite a long time.

At the start of the war, several hundred trials were ongoing in Ukraine. Most of these trials were in oncology, equally distributed between phase 1, phase 2/3, and phase 3 trials. Clinical trial management during the first chaotic stage reflects gradual adjustment to the unfolding disaster. It is a stage when the actors cannot yet fully appreciate the size and the effects of the challenge. Contact with a sponsor is either nonexistent, sporadic, or inadequate. In this situation, the most important task is to collect information and to evaluate the effect of the situation on the staff, the healthcare facilities, the patients, and the social infrastructure.

How can you make ethically motivated, correct emergency clinical trial decisions? After evaluating the situation, you might conclude that clinical activities are impossible because the hospital was destroyed and no personnel are available. If you conclude that the clinical trial treatment could continue but the support is lacking (to treat possible serious adverse reactions, for example), a second possibility is to stop the clinical trial and provide the best possible treatment outside the trial. This is done to benefit the participants.

However, if your facility remains intact and you have adequate staff, you should continue the already initiated investigative treatment and adhere to the trial documentation as much as possible. So, many clinical trials continue to accrue and treat patients according to GCP standards, either in Ukraine or in neighboring countries such as Poland.

The sponsor is also following this unfolding catastrophe. What can the sponsor do if contact with the investigator site is severed, or communication is inadequate? Gathering information concerning the effects of the situation on the staff, healthcare facilities, and social infrastructure is of paramount importance to make an ethical and scientific evaluation of possible changes in the protocol without destroying the scientific value of the study.

Very early in the war, well-known American ethicist Arthur Caplan published the paper Should Pharmaceutical Companies Continue to Do Business in Russia? This paper questioned whether Western pharmaceutical companies should continue clinical trials that had already been launched, start new clinical trials, or sell their products in Russia. His conclusion was essentially “no” because medicine and science are controlled by political forces, and their use (for good or evil) is driven by political considerations. Each doctor, scientist, and scientific society must take a corresponding stand. Caplan’s article adds that only minimizing the harm to existing subjects for a short period of time is necessary. Similarly, no sale of medicines or therapies should occur in Russia except for lifesaving products.

Several hundred clinical studies in Russia were discontinued as a result of these economic sanctions. At the start of the war, a large number of trials were ongoing, some were ongoing but not recruiting, and others were already closing recruitment. Many companies stopped patient accrual immediately following declaration of the economic sanctions. Clinical trials could continue using stockpiled drugs for a time, but stockpiled drugs would be used up quickly.

This war marks the first time that clinical trials and clinical trial management are so clearly part of economic sanctions. This is a new and disastrous method of economic warfare that severs many well-developed, international scientific-medical cooperative endeavors. (Previously, as in the Cold War, socialist countries did not have well-developed economic, scientific, and healthcare contacts with the Western world and lived in separate, parallel worlds.)

Russian investigators have lost contact with their sponsors. They cannot send out biological materials or obtain the results of biological tests, which means they cannot decide whether a patient is eligible for a trial or not. Trial management has become very difficult. All GCP-level clinical trials sponsored by Western companies were or soon will be stopped in Russia.

We can draw some conclusions from these circumstances: The decision of where to place and when to stop entering new patients into a trial is a combined scientific and strategic decision by the sponsor. So, stopping patient accrual into ongoing trials in the Russian Federation as part of the economic sanctions is ethically acceptable.

However, we must look differently at patients who already signed informed consent and were entered into clinical trials before the war began. We should consider these subjects a patient population that is vulnerable due to the economic conflict. Our opinion is that it is ethically imperative to continue the already initiated investigational treatment if it is possible and if it is considered beneficial for the patients to remain in the study.

This recommendation aligns with existing ethical concepts. For example, the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans jointly prepared by CIOMS and the World Health Organization in 2016 includes this important statement: “The judgment that groups are vulnerable is context dependent and requires empirical evidence to document the need for special protection.” Based on this principle, the IFAPP Ethical Working Group concluded that patients who were already enrolled into clinical trials in both Ukraine and in Russia should be considered a specific vulnerable patient population and suggested that already initiated treatments should be continued if possible and if beneficial for the patients.

The conclusion that continuing already initiated trial treatments for the benefit of the patients is a primary ethical obligation of clinical investigators in case of war, economic sanctions, or natural catastrophe needs further explanation. Patients entering randomized trials know that patients in the control group receive either the best available treatment or occasionally placebo, and that those receiving the investigational treatment might not obtain benefit and might even develop severe side effects. The patients agreed and signed an Informed Consent hoping to obtain remedy and benefit from participating in the clinical trial. Many of the patients enrolled in trials in these two countries are seriously sick oncologic patients for whom their investigational treatment is the last possibility for effective therapy. In, and especially during, difficult times, sponsors and investigators should sustain the hopes of patients, not abandon them.

Finally, we must also consider the increasing potential of natural catastrophes to interfere with the performance of clinical trials in the future. Natural catastrophes usually cause damage similar to the damage resulting from modern warfare. Therefore, much of the experience gathered from clinical management of patients in times of war could also be applied during natural (not manmade) catastrophes.