Hand-In-Hand with Companion Diagnostics: The Past, The Present, The Future

Elizabeth Mansfield IVD Consulting

ompanion diagnostics are a class of diagnostic devices that has become important not only in personalizing therapy for patients, but also for developers of therapeutic products, who must now consider not only development of the drug or biologic, but also development of a diagnostic test to identify or manage patients who use the therapeutic product.

The Companion Diagnostic Paradigm

FDA explained that it would require the simultaneous approval of a therapeutic product and a companion diagnostic when a companion diagnostic is required. This requirement was tied to the federal requirements for drug labeling which state that product labeling must include information about:

- specific tests necessary for selection or monitoring of patients who need a drug,

- dosage modifications in special patient populations (e.g., in groups defined by genetic characteristics), and

- the identity of any laboratory test(s) helpful in following a patient’s response or in identifying possible adverse reactions.

In addition to the companion diagnostic device guidance published in 2014, a draft guidance titled Principles for Codevelopment of an In Vitro Companion Diagnostic Device with a Therapeutic Product was published in 2016 and explained more fully the FDA’s thinking on how therapeutic and diagnostic device product developers could go about the “codevelopment” process. This draft guidance laid out (admittedly idealized) pathways and attempted to provide advice on how trials intended to support the approval of both the therapeutic product and the diagnostic might be designed, and how developers might think about the development process when the need for a companion diagnostic was identified earlier or later in the therapeutic product development cycle.

The companion diagnostic policy was met with some skepticism, especially by the regulated therapeutic product industry, in that it placed the responsibility on therapeutic developers to ensure that a diagnostic device would be available to be approved by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), the FDA Center that regulates medical devices. Therapeutic developers were uncertain when or whether the policy would apply to them and who would make the decision that a companion diagnostic was required. They were generally unfamiliar with how medical devices are regulated and did not have the necessary in-house expertise to carry out the diagnostic development themselves. In addition, at the time the policy was put into place, it was only applicable in the US; as a result, the US requirements differed from those of other regulatory jurisdictions, and this was said to have made navigating the global therapeutic approval requirements more complicated.

As of this writing, multiple regulatory jurisdictions have adopted the companion diagnostic paradigm, in recognition of the safety issues presented when a test is used to help select or manage a therapeutic product. Most therapeutic product developers now understand the principles of companion diagnostic development, although putting them into practice is still challenging to many.

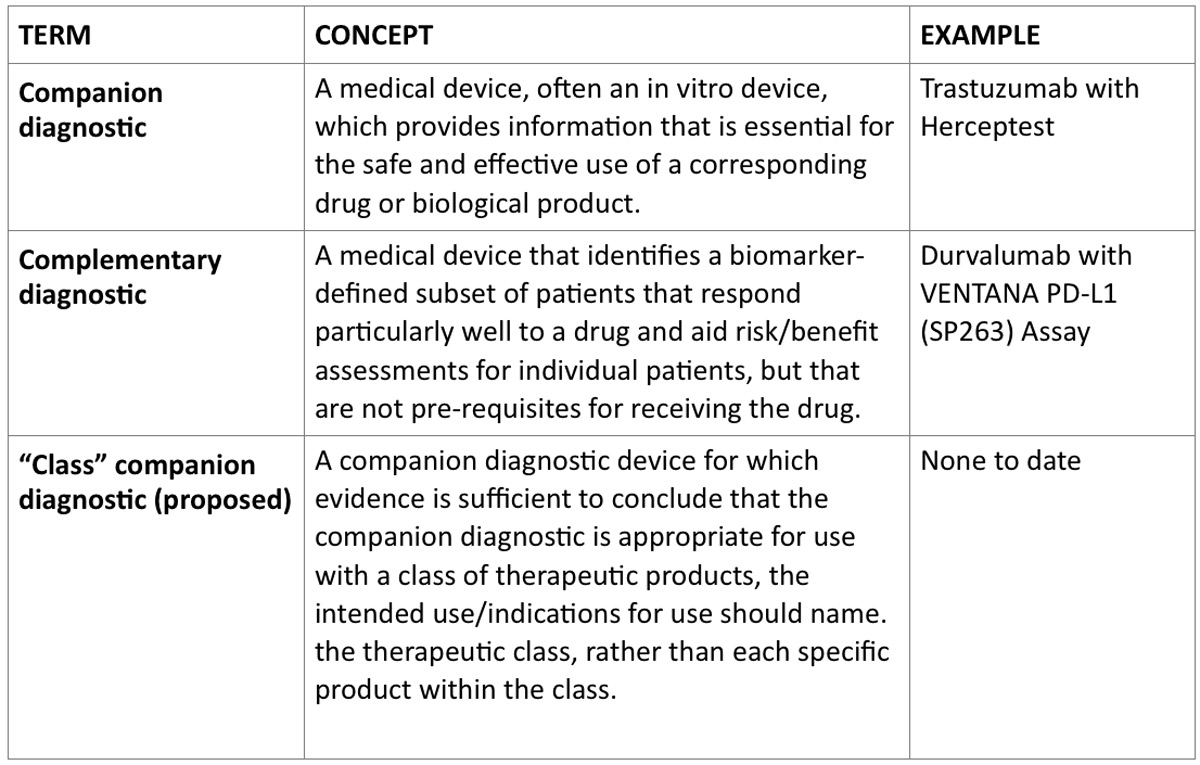

The concept of a “complementary diagnostic” has been developed, and tests have been approved, whereby a diagnostic test may be authorized for use with a specific therapeutic product but is not considered to be a companion diagnostic. The exact definition of what constitutes a complementary diagnostic has not been clarified by FDA, nor has a draft guidance been issued to date; a draft definition, however, is available. It states that a complementary diagnostic device is one that can “identify a biomarker-defined subset of patients that respond particularly well to a drug and aid risk/benefit assessments for individual patients, but that are not pre-requisites for receiving the drug.”

Examples of authorized complementary diagnostics suggest that a complementary diagnostic is one that can inform which patients within the indicated population might do somewhat better or not as well when treated with a specific therapeutic product. Complementary diagnostics are not required for approval of any therapeutic product. However, if a therapeutic product developer wishes to either de-risk development by having a diagnostic available in case a companion diagnostic is required or attempt to improve the benefit-risk balance of a therapeutic product, then a complementary diagnostic development program could be considered.

Issues with Development and Use of Companion Diagnostics

Published data indicate that, even though many oncology drugs are offered with approved companion diagnostics, a proportion of physicians do not actually order or use results from a companion diagnostic test where one is indicated in the therapeutic product label. Instead, many may select a test that is for the correct marker but not validated for the particular therapy for which information is sought. These facts suggest that while FDA and medical product companies are highly focused on pairing a therapeutic product with an appropriate companion diagnostic, in the real world of clinical practice there may be either ignorance or confusion over the companion diagnostic paradigm, or there are other factors, perhaps related to cost, that result in failure to order an FDA-approved test for what might be markers of effective therapy.

Some Solutions for Companion Diagnostics and Their Limitations

NGS testing, however, has not solved the issue of multiple tests needed for markers that are only identified through protein or RNA expression (one of the newer types of companion diagnostic markers), among others. There is no identified technology yet that would cover all possibilities for in vitro diagnostic markers. Therefore, the problem of the multiplicity of tests needed in order to identify appropriate tests for patients will likely remain unresolved in the near future.

Another emerging area of in vitro diagnostic test development is “liquid biopsy.” Here, companion diagnostic markers, especially genomic ones, are tested for directly from peripheral blood samples. The sensitivity of NGS technology has developed to such an extent that detection of tumor DNA fragments shed into the circulation can be reliably identified and any mutations or other alterations of interest can be detected. This approach solves the problem of sample availability, but again does not (yet) address markers that are not genomic.

Another approach that is being further developed is the direct detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the bloodstream. This approach utilizes the isolation of individual tumor cells for in vitro diagnostic analysis, potentially allowing for highly specific testing for markers of interest. In addition, if the tumor cells themselves are available for analysis, testing beyond genomic markers is feasible. To date, one test for circulating tumor DNA has been approved as a companion diagnostic but only for a single marker (EGFR mutations), and CTC testing has been authorized for use in prognosis of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer, but not as a companion diagnostic.

Recently, FDA has proposed to take on an option identified in the original companion diagnostic guidance: the development of companion diagnostics for a class of drugs. This type of companion diagnostic would be one test that meets the regulatory requirements for a class of therapeutic products rather than a specific product. The draft guidance, Developing and Labeling In vitro Companion Diagnostic Devices for a Specific Group or Class of Oncology Therapeutic Products, specifically proposes a single diagnostic device approval to stand as the requisite approval needed for most or all drugs requiring measurement of the same biomarker.

This is an attractive idea for certain types of markers, e.g., those where only the presence or absence of a genomic mutation is identified, because it seems quite likely that a single test could have adequate performance characteristics to function in this way. Certain considerations, such as the lowest level of detectable mutation, would need to be optimized, and the test would likely need to be used in trials of one or more of the therapeutic products in the class. For other types of tests, e.g., the PD-L1 tests that may have different sensitivities, cut-off values, and cross-reactivities, it may be significantly more difficult to infer or prove that one test would suffice across the entire class. FDA has not finalized the guidance, and if it does, it seems likely that its applicability would be limited to certain markers.

The class approval approach may help to relieve the need for multiple tests to identify a possible therapeutic candidate within a class of drugs, but it does not directly address the desire to have multiple approved companion diagnostic tests for the same therapeutic product. This has been identified as a problem, because many clinical laboratories may only have a single manufacturer’s test system in operation, due to capital equipment costs, reagent-rental deals, etc. To date, the wide availability of laboratory developed tests (or LDTs), which are in vitro diagnostic tests that are designed, manufactured, and used within a single laboratory but under FDA’s current policy of enforcement discretion (i.e., subject to FDA regulation, but FDA has chosen not to enforce its authority), have in part filled the gap. But FDA may need to examine incentives and opportunities to have more than one test approved for a given therapeutic product.

The “LDT issue” of whether FDA actually has explicit authority to regulate LDTs, and if so, how they will be regulated, has been referred to the US Congress for definitive resolution through a new statute. The discussion draft of a bill (proposed as the “VALID” Act) would treat most LDTs that act as companion diagnostics as high-risk devices that require FDA approval. Although LDTs on the market at the time of any future enactment would be grandfathered (continued offering allowed without FDA review), any significant changes to a grandfathered test would require FDA review, and any newly offered test would also require premarket review and authorization. The incentives for, and the ability of, laboratories to comply and to offer tests as companion diagnostics could be affected by the legislation. Therefore, considerable thought will need to be put towards optimizing the companion diagnostic framework as this process moves forward.

Summary

References available upon request.