AGAPE Strategic Solutions of Maryland, LLC

People Empowering People for Inclusion Now, LLC

People Empowering People for Inclusion Now, LLC

ACE Regulatory Affairs Consulting, LLC

here is no single solution to solve the challenge of recruiting and retaining participants in clinical research, and especially for those who have been underrepresented or historically excluded from participation. The need is great because such underrepresentation can affect drug utilization and patient experience in terms of product safety, efficacy, and quality. It can also materially impact the applicability of results to broader patient populations and the cost of research innovation. This challenge will not be effectively addressed or solved by incremental adjustments to recruitment approaches, particularly for individuals or groups most impacted by life-threatening health conditions in the real world. More diverse and inclusive representation would benefit everyone in the clinical research and product development process, including patients themselves.

What Was the Approach?

The leaders of this start-up company sought to collect perspectives from family, friends, and associates in a convenience (or Pulse) survey prior to developing recruitment engagement practices and technology archetypes. A convenience survey is a nonprobability method of selecting individuals who are available and accessible to provide quick or convenient responses in a study. This method involves finding participants to take part in a research study by the easiest means possible. Convenience sampling is practical when some data are better than no data at all, and it facilitates recruitment based on participant availability, speed, and efficient use of resources.

The aim of the company was to collect respondents’ thoughts to inform hypotheses around clinical research participation and the use of digital technologies. They wanted to better understand perspectives about engagement and obtain early input to inform frameworks for product development using a community-driven participatory action approach.

A total of 124 individuals responded to email and text message requests to participate in this study. Access to the Pulse survey was enabled using an online platform with a mobile phone, computer, or other digital device. Information was collected via a 16-item survey that asked about clinical trial awareness, participation, and engagement prior to answering the survey. Respondents were also asked about their satisfaction with the healthcare providers, the healthcare system, and overall trust in the research process. Additional questions assessed their perceptions about using a digital platform to engage in clinical research, willingness to participate in trials that use digital technologies, and opportunities to collaborate with the study team and other individuals in the community.

What Were the Results?

The responses to the Pulse Survey, conducted from April 6 to May 5, 2023, included results from 124 individuals from a diverse array of racial/ethnic groups and age ranges. Specifically, 60% self-reported as Black or African-American, 19% as White, 6% as Latino, 5% as Asian, and 2% as Other. The median age was 46 years old (y.o.), with 19% reporting 60 y.o. or older, 34% between 46-59 y.o., 25% between 36-45 y.o., and 19% under 35 y.o. Data on gender, disabilities, or other demographics were not collected due to concerns about response burden. The number of personal questions was deliberately kept low so as to not discourage participation. However, this proved to be a costly lesson because additional demographic information, especially on gender, would have provided more insight on variations in response by groups. Statistical significance was not observed due to low sample sizes, except for statistically significant differences observed across racial groups. These results were not meant to be generalizable to the broader US population, but to provide useful and exploratory insight.

Nearly all (93%) of the participants had heard about clinical research as defined as either investigational clinical trials or real-world observational research, with 42% hearing about it through a family member or friend. Far fewer (14%) heard about it through their doctor or healthcare provider. About 10% learned about it through a research portal/network, newspaper mailing or advertisement, or in some other way. The lowest level of awareness was through social media or digital technology, such as a search engine (6% and 4%, respectively).

The overall results also indicated that 81% of the respondents had never been in a clinical study before. Of the 19% (n=24) who had participated, all indicated that they understood the purpose of the study and 92% said that they liked participating in it. However, only 58% reported receiving a benefit from participating. When asked if they would participate in a research study in the future if it was convenient (i.e., accessible or easy to participate in), 77% (n=88) of respondents said that they would and a tenth indicated that it did not matter. (This data is missing for/from 14 respondents.)

The perception of benefit varied by race and ethnicity. When asked if they liked the research experience, 93% (or 15) of the Black respondents who had participated in a study before said that they liked the experience as compared to 100% in the other racial/ethnic groups. Whites reported that they would be willing to participate if convenient (83%), as compared to about 75% for both the Black and Latino groups.

Technology in Clinical Research

Overall, a majority (85%) indicated that they were “somewhat to very comfortable” using a device, such as a cell phone or computer, in a clinical study; 11% were somewhat comfortable, and 4% said that it did not matter. None of the participants expressed discomfort in using a device, and only a small number (7%) in the Black group indicated that it did not matter. Whites reported the highest comfort in using a device (78%) as compared to Blacks (66%). Those under 46 years of age were more comfortable using a device or technology as compared to respondents who were 46 years or older (52% vs 48%, respectively).

Trust in Clinical Research

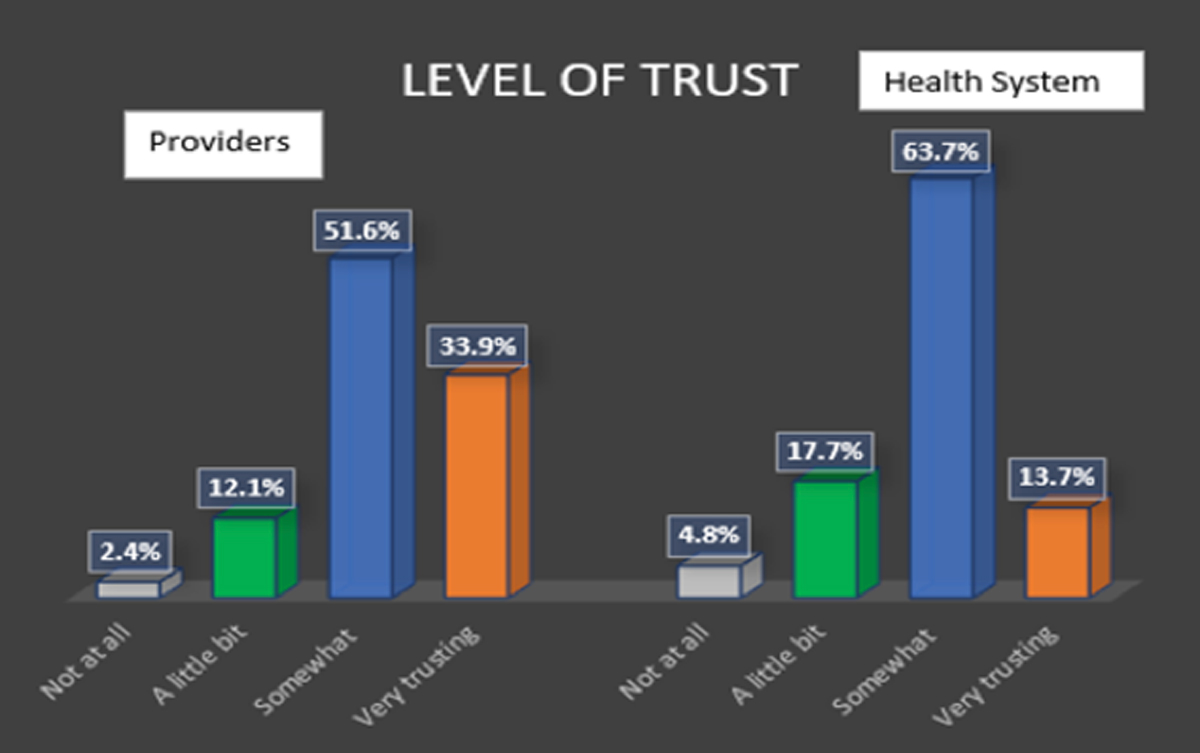

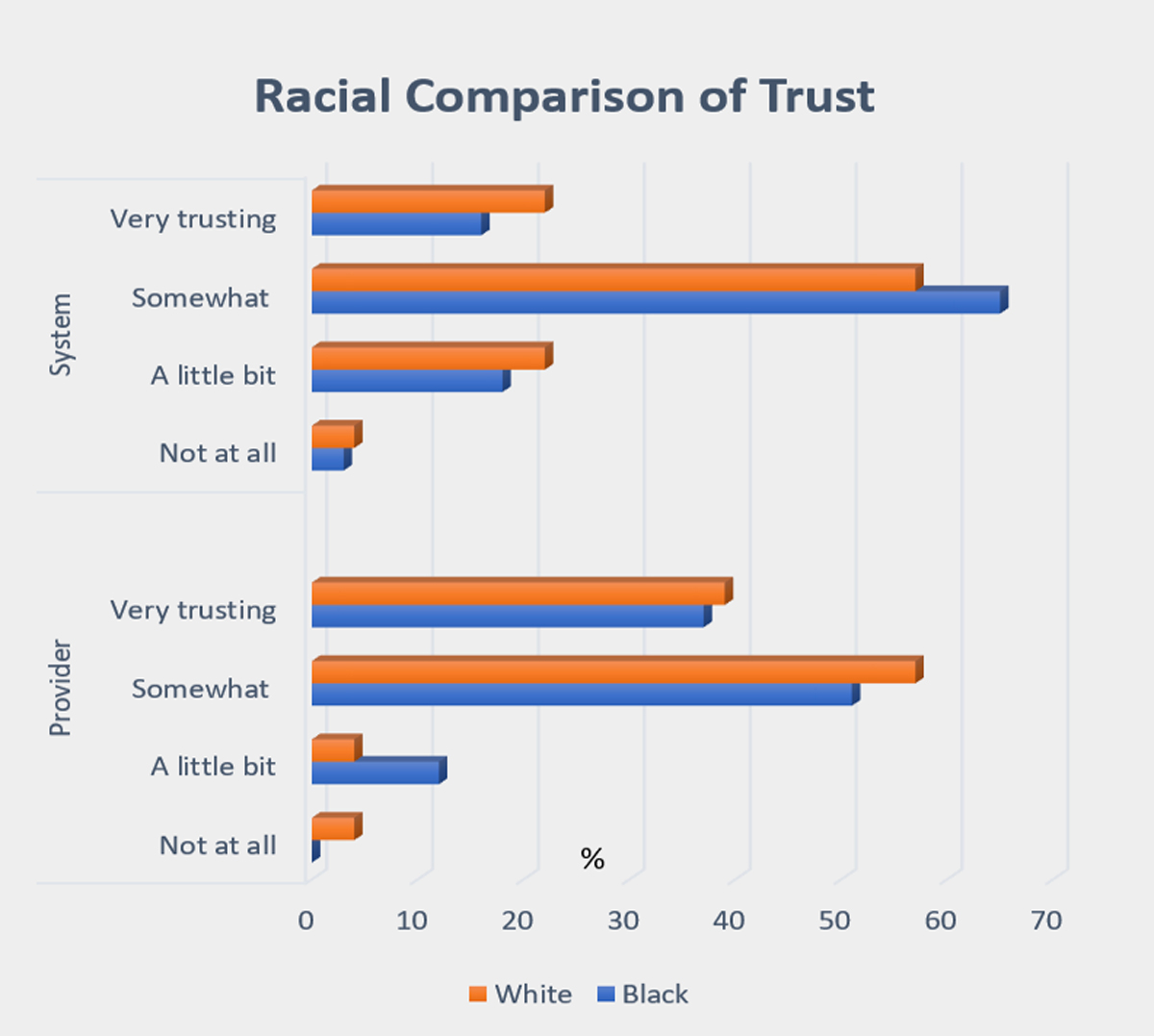

Participants were asked about how well they trusted their healthcare provider and the healthcare system in which they received care (see Figure 1). Overall, 86% of total respondents indicated that they were “somewhat or very trusting” of their providers. The number was lower (77%) when asked about the same level of trust with the healthcare system.

Whites had higher responses of not trusting providers or the system at all as compared to Blacks. The combined group of Asians and Hispanics reported the lowest level of trust of providers at 36%. However, the number of respondents in this group was too small for comparative purposes (n=5).

Now What?

Based on the results of this Pulse survey, questions linger about the significance and implications of efforts to increase inclusion in clinical research recruitment and engagement based on a convenience sample of family, friends, and associates. Some implications are:

- What were the reasons why respondents may have chosen to not participate in clinical research?

- Would they have been more willing to participate if they were provided the opportunity by healthcare professionals or individuals that they trusted?

- What was the reason for having (or not having) trust in the healthcare system?

- To what extent did personal negative encounters or tales of bad experiences in the past factor into perceptions of distrust?

- Can obstacles be overcome through clinical research education, health literacy navigation, and engagement opportunities from more trusted sources?

One of the key factors associated with inclusion in clinical research is the extent to which people found value in the research process and trusted their healthcare provider or systems with which they were engaged. Clinical Research as a Care Option (CRAACO) is one method of introducing suitable patients to clinical trials by their healthcare providers to improve participation in research opportunities. The purpose is to build an integrated approach to communicating with patients about trials using more trusted avenues and sources, e.g., digital social media, go-to platforms, and educational programs. This may also help to build more concordant relationships based on agreement or consistency between the healthcare system, providers, and patients through transparency, better coordination, and information sharing.

A study published in 2006 in the Public Library of Science Medicine (PLoS Med) examined the willingness of individuals across various racial and ethnic groups to participate in health research. Although there were some between-group variations in the willingness to participate, the authors suggest that more focus should be placed on providing information and access to research rather than assuming that underrepresented groups are less willing to participate. Individuals can and will determine the value of participating or engaging for themselves when presented with information from trusted sources and the opportunities to make informed choices.

These study results and potential implications may provide further insight into approaches for early patient engagement and design of digital resources to improve the collection of patient insight and access to clinical research opportunities. This may be particularly important for assessment prior to drug or product commercialization or real-world implementation of interventions. Early insights may aid in discovering more validated ways of integrating new technologies into practical applications, to thereby enable better participant engagement, support CRAACO strategies, or adapt to user experiences for sustainability throughout the clinical research process and afterwards. For example, digital product developers can be more proactive in gathering participant feedback pertaining to the use of live aid assistance (“bot” or robotic) features earlier and throughout the development process to better understand content navigation preferences. This can provide insight to enable users with more convenient and quicker access to information to make decisions, given hectic work schedules, home priorities, or other lifestyle conditions.

Other digital options may be to provide mechanisms for participants to conveniently provide responses or collect data, such as using laptops/cell phones to answer study questions, wearable technologies for real-time monitoring, or gamification incentives for completing patient-reported outcome surveys embedded in study protocols. Questions and issues important to participants or product use may be explored much earlier in the research process to avoid technical redesign or protocol adjustments, thereby saving time, money, and energy. In this way, research sponsors and device developers would be better able to engage with participants and potential users of innovative medicines and digital devices to determine effectiveness.

The goal of this study was to inform one company about inclusive research approaches for data collection, proof of concept for product design, and digital engagement strategies from diverse communities in which they seek to engage and offer technology solutions. Much more exploration is needed on participant input into research design and early adoption of new innovations to improve outcomes and reduce disparities.