Six Guiding Principles for Pharmaceutical Companies to Achieve Global Quality

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

OVID-19 has ushered in a new age of urgency for pharmaceutical companies, one that simultaneously requires increased regulatory flexibility and unwavering commitment to quality. Now more than ever, companies recognize the importance of ensuring quality at each of their units and sites around the world. To achieve oversight of their quality outputs across the globe under these challenging circumstances, organizations must globalize the quality function rapidly but also thoughtfully.

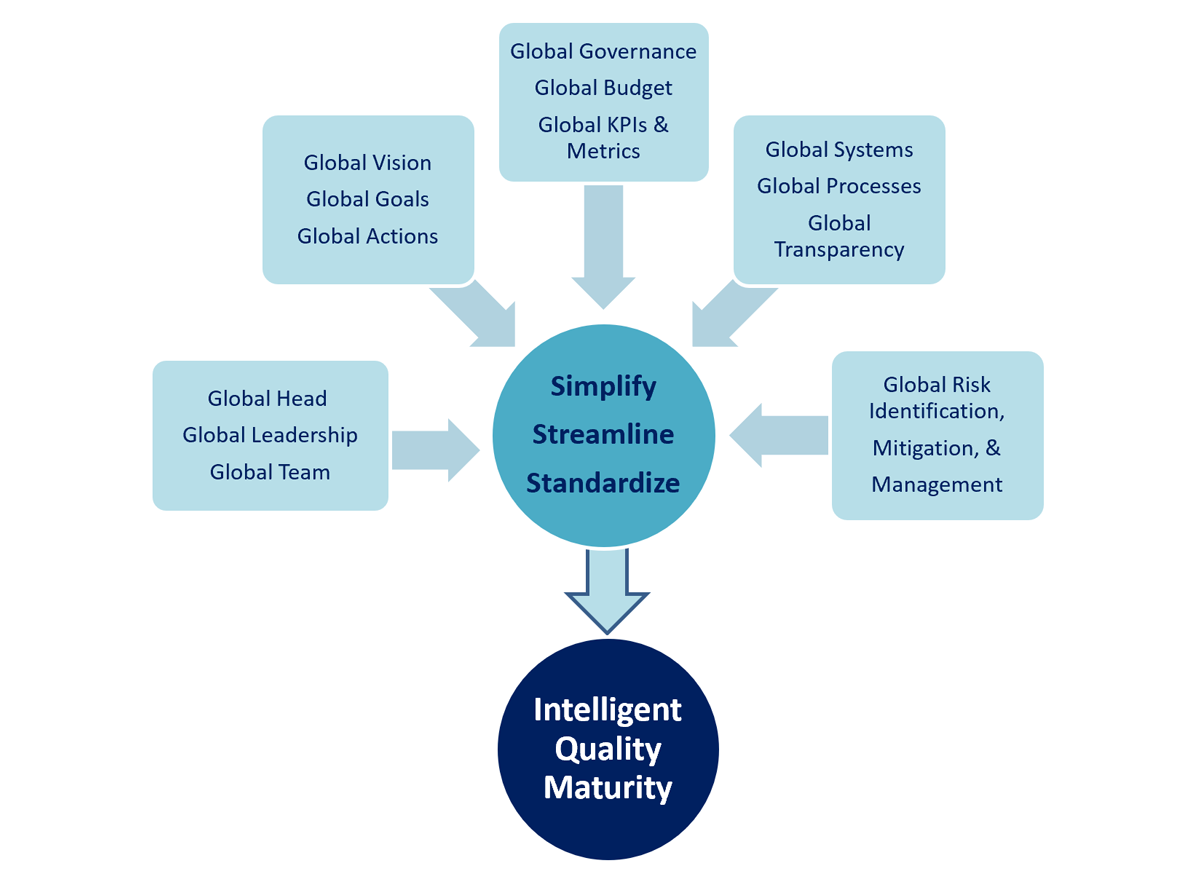

The Guiding Principles

The first step in a company’s global quality transformation is to select a Global Head, who will be responsible for leading the globalization effort and the Global Quality Team. The Global Head’s effort begins with mapping the organization’s existing quality ecosystem. Most companies grow in fragments; when new departments and positions are created, essential quality functions become siloed and roles and responsibilities become obscured.

As a result, quality units adopt different nomenclature for similar responsibilities, such as Quality Assurance (QA) or Quality Management (QM), making it challenging to identify who does what. Therefore, it is critical for a company to begin its global quality journey by identifying all units and personnel responsible for any aspect of quality, so all are included in the globalization journey. The individuals identified will make up the Global Quality Team; their cohesion and feelings of ownership will be key to the success of quality activities. The Global Head should also establish a Global Leadership Team, which will drive the company’s globalization efforts.

Once mapped, the typical company’s quality ecosystem often appears so fragmented and complex that it is tempting to start over from scratch, creating orderly new groups and lines of command. This is rarely feasible, however. By building upon reporting lines that already work well, a company can minimize the level of threat felt by staff members, making them more receptive to change. Often, simply standardizing the nomenclature for quality functions and roles is immensely helpful.

For instance, all units within the company that carry out a similar GxP quality activity, such as good clinical practice (GCP) quality, can be functionally aligned into a single global quality unit with standardized nomenclature for each role, thus clarifying who is accountable for quality tasks. After functional alignment is complete, a kick-off celebration can introduce the newly established Global Quality Team.

The Global Quality Team is ideally situated to help identify and prioritize company-wide quality risks. To gather information about quality pain points, companies can conduct workshops or surveys involving Global Quality Team members and other GxP functional area stakeholders. The comprehensive picture of quality risks and pain points that emerges from such research is invaluable; however, an organization cannot tackle all risks at once and hence needs to prioritize them based on criticality.

Some risks—such as outstanding compliance issues—must obviously be addressed immediately. Other problems, while less urgent, may still be important and also have straightforward solutions. For example, establishing a global audit program that actively engages GxP functional areas while transparently providing insights into its findings may represent a quick win for the new Global Quality Team.

Once the company has decided which problems to target first, the Global Quality Team should develop action plans to address them. Such action plans tend to be well received, as staff understand that the plans represent input and consideration from their colleagues throughout the company. The individuals who develop the solutions are committed to them, and their colleagues tend to be more receptive to action plans they know were developed by people familiar with day-to-day operations. In short, developing solutions internally drives inclusion and ownership, and teams and subject matter experts appreciate the opportunity to be recognized for their knowledge and ingenuity.

The Global Head should help develop a global workstream for each action plan and also identify a champion among the individuals responsible for carrying it out. The Global Head and workstreams champions should then take care to socialize all strategies and action plans with the functional area leads whose teams will support and engage with the Global Quality Team as they perform their work. Invariably, some criticisms of quality action plans will arise. But engaging critics in the process of change often leads to greater harmony and better outcomes. As action plans are carried out, the Global Head and Global Quality Leadership Team will provide oversight and periodic reviews of each workstream’s progress. This ongoing attention will ensure that teams receive the support and empowerment they need to achieve their quality goals.

Along with the Global Head, the Global Quality Leadership Team develops the company’s global quality vision, goals, and strategic imperatives. In addition to providing direction for the larger Global Quality Team, the Global Quality Leadership Team—which should include lead representatives of a company’s key quality units and geographical sites—is responsible for monitoring the company’s progress toward meeting goals and for helping resolve any challenges that emerge. It must also establish and publicize an escalation process for addressing challenges and making decisions. In charting a course for the future, the Global Quality Leadership Team should consider hiring consultants to compare the company’s practices to those of peer organizations. This type of benchmarking can help a company evaluate its baseline performance and identify how its journey toward quality maturity might proceed (see Figure 1).

It is essential that everyone at a company has a clear understanding of how quality works across the organization and how the company evaluates its quality barometer. To facilitate such transparency, GxP-related standard operating procedures, templates, training programs, and tools for managing quality documents should be harmonized across the organization. In addition, it is crucial to identify key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics by which the organization can track progress, and to create transparency dashboards that allow such indicators to be viewed at a glance. This enables the Global Quality Leadership Team and others in management to review metrics gathered from global audit and inspection activities, as well as quality events, across manufacturing facilities and GxP functional areas.

Equally important is sharing this information with relevant GxP functional areas and leads, to increase their awareness of how well the quality activities they and their peers are responsible for are being executed. For example, when quality problems are identified at one site, other sites should be informed, and co-corrective actions should be taken throughout the company to ensure that the same issues do not recur elsewhere. Such transparency fosters staff members’ feelings of ownership of quality metrics and outcomes within GxP functional areas, increasing their commitment to addressing quality risks and driving compliance excellence.

Henrietta Ukwu MD, FACP, FRAPS, serves as SVP, Chief Regulatory Officer & Global Head, Global Quality and Global Regulatory Affairs, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. She thanks Kristen Bequeath and Christina Sarvary, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., for their helpful comments in developing this manuscript, and Kristin Harper, of Harper Health & Science Communications, LLC, for providing writing and editorial support in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.