Dinorah Villanueva

Janssen Research and Development

otential differences among racial and ethnic groups in the metabolism, effectiveness, and side-effect profiles of novel investigational medicinal products (IMPs) underscore the need to enroll participants from diverse populations into clinical trials. If medical care is not tailored to all who need it, certain categories of patients will be left behind. Regulators have realized this, and sponsors must be prepared to comply with new regulatory expectations. This article addresses the proactive steps sponsors can take to prepare for the submission of clinical trial diversity plans to regulators, and more specifically the US FDA.

Sponsors and regulators have reached a consensus about the criticality of diversity in clinical research. For example, Health Canada has issued a questionnaire to sponsors to address disaggregated clinical trial data by race, gender, and age. Recent MHRA consultations have proposed the inclusion of legislative requirements to support diversity in clinical trials. Most notably, in April 2022 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released their draft guidance on Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials. Finally, in December 2022, several clinical trial diversity-related provisions were included in the US Omnibus funding bill—a reaffirmation of and strong congressional mandate for the role of clinical trial diversity. Thus, the initial diversity plan guidance and subsequent legislative reforms represent a step toward a future in which representative and inclusive clinical trials are a prerequisite for a successful regulatory submission.

What Can Sponsors Do to Prepare for Diversity Plan Submissions?

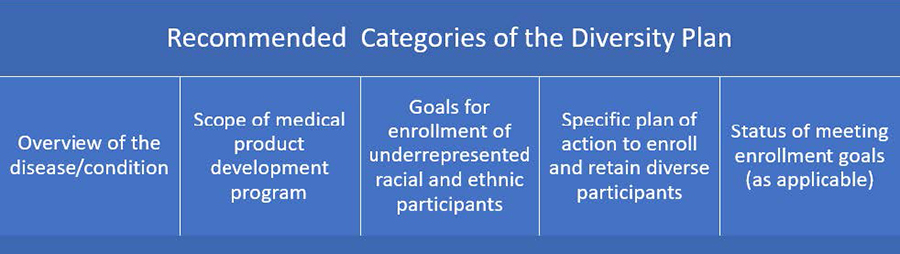

Below are preliminary learnings from initial efforts to prepare for these submissions. While the categories in italics reflect what was included in the April 2022 draft guidance and may be subject to change in future iterations, we assume that the content of submissions—and therefore sponsor considerations—will remain largely the same.

The Specific Plan to Retain and Enroll Diverse Participants category suggests that sponsors leverage local laboratories and imaging facilities, local healthcare providers, and telehealth to foster community engagement and reduce trial participation burdens. However, many sponsors currently rely on emergency guidance from the pandemic to address many of these decentralized and patient-centered capabilities. As part of the Omnibus legislation, the agency will both hold a workshop on clinical trial disruption mitigation recommendations in the wake of COVID and issue guidance regarding how decentralized clinical trials (DCTs) can drive the engagement, enrollment, and retention of meaningfully diverse clinical trial populations. These learnings, among other novel trial-related guidance (including the other anticipated DCT guidance), represent a helpful development for sponsors and patients alike. However, despite forthcoming guidance, sponsors must be comfortable operating in a risk-based manner and without prescriptive guidance for each novel and decentralized trial component. To mitigate risk, sponsors should implement existing site qualification processes for traditional sites to ensure that local site models are adhering to the same expectations. Consideration should also be given to assess whether any processes need to be defined or updated to support clinical conduct utilizing local models, and audits would need to be planned to evaluate novel and decentralized trial components. Internal stakeholders should include clinical operations, feasibility, and patient/community engagement to provide input on novel research methods. The more seamlessly sponsors can utilize local sites who may be research-naïve, and validate home healthcare capabilities, the more likely they will be able to meet the objectives set forth in the plan. However, the onus is not on sponsors alone; regulators must provide a risk-based framework that reflects learnings for the novel trial components addressed in the diversity plan guidance to reduce study burden.

Considering the appropriate regulatory intelligence infrastructure and internal trackers to leverage feedback from diversity plan submissions is another important step. For example, if the agency appears to prefer a certain epidemiological methodology or data source, it would be beneficial to other study teams to consider this feedback for their submissions. While certainly there will be variation of FDA feedback by study stage and therapeutic area, common themes will likely emerge. A regulatory intelligence infrastructure can also be augmented by the annual summary reports the FDA will release on the progress of diversity in clinical research initiatives.

Sponsors can consider how they leverage community engagement forums to ensure that diversity goals are met. For example, community feedback might lead a sponsor to ensure that clinical trial materials are translated into the languages which reflect a proposed site’s community. Sponsors can help sites, but sites will also own part of the responsibility in this process. Sites will need to know their community and how to develop tactics to approach underserved patients. For example, we have observed that certain sites leverage community leaders and forums (such as local churches) as a grassroots method to increase clinical trial awareness in an organic and trustworthy manner.

Unanswered Questions from the Diversity Plan Guidance

FDA’s draft diversity plan guidance provides a strong initial framework for these novel submissions; however, several unanswered questions remain. If FDA clarifies these questions in future guidance, sponsors can more effectively tailor development programs to meet the goals and intent of the diversity plan framework.

While it is important to consider diversity for every single trial, diversity plan submissions will require input from an indication-level perspective, and the agency should clarify in the final guidance the interplay between indication-level considerations and individual protocol-level diversity plan submissions.

The guidance relies upon race and ethnicity categories as defined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Unfortunately, these categories are relatively restrictive and do not provide sponsors with the ability to reflect patient populations who identify as multiracial or multiethnic. In June, OMB announced their intention to update the standards and categories for the collection of race and ethnicity data by Summer 2024. Stakeholders should use this opportunity to inform the creation of more representative and tailored categories for data collection and its impact on data analysis.

Sponsors would benefit from more direction as to the recommended location of the diversity plan in submissions and how sponsors should update them. As an IMP matures from early-stage development to later stage, there will be different considerations for diversity plan submissions and the diversity plan will evolve alongside the IMP.

The FDA diversity plan is primarily intended for US-based populations. However, for certain multiregional trials additional clarity will be needed on how ex-US data can support a diversity plan submission. As other regulators will likely emulate the FDA, it is crucial that the agency share best practices with other health authorities. There are also areas where international collaboration is required such as registries and other data sources that represent patients outside the US with a particular condition. Beyond multiregional data sources, in general, additional input from the agency about preferred methodologies and standards for databases to inform diversity plan submissions would help address uncertainties.

Finally, the agency should continue to vigorously engage stakeholders to share learnings and updated best practices. For example, in scenarios where sponsors perform post-approval studies because they failed to meet diversity plan goals prior to approval, the agency can monitor common pitfalls that appear to be leading to such failures and proactively advise other sponsors. Such learnings can be shared via annual reports, workshops, and other means of communication. However, this responsibility is not the agency’s alone. It would be beneficial to all if sponsors also shared reflections (and failures) with the broader drug development community.