Janssen Research and Development, LLC, A Johnson and Johnson Company

Merck Healthcare KGaA

Merck & Co., Inc.

Novartis

Biogen

BMS

BMS

Astellas

Novartis

eal-world evidence (RWE) can potentially complement clinical trials and support regulatory decision-making, but only if underlying real-world data (RWD) are sufficiently relevant and reliable and if quality measures are applied during collection, handling, and processing. Regulators and other stakeholders would benefit from alignment of frameworks for evaluating RWD quality. As a first step towards this, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a Data Quality Framework (DQF) in October 2023, with a real-world evidence DQF annex expected in 2024. In response, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) sought to assess available tools for implementing the DQF, with the goal of trying to operationalize the framework and informing future efforts. EFPIA’s findings and recommendations were presented and discussed with EMA in May 2024 and are illustrated in this article.

The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) Integrated Evidence Generation and Use (IEGU) Data Quality sub-Working Group welcomes the regulatory authorities’ initiative to introduce frameworks that maximize opportunities for RWD to be leveraged to generate evidence for regulatory decision-making. Our experience is that, in practice, study developers and other stakeholders will need tools to integrate data quality frameworks into their work processes to meet regulators’ expectations for quality assessments and reporting. Therefore, we sought to assess available tools for implementing the DQF, with the goal of trying to operationalize the framework and offering suggestions for its improvement. Implementation tools, inclusive of tools generating quantitative output (e.g., programs or code) and checklists, and other frameworks are needed to determine whether quantitative and qualitative aspects of data quality are achieved; that is, whether the data are fit for purpose in addressing a specific regulatory research question. Ideally, available implementation tools and frameworks would align with the DQF dimensions for ease of use by the wide range of stakeholders who will generate and use RWD, including disease registry holders and medicines developers.

Preliminary findings of this EFPIA assessment for implementing EMA’s DQF were presented at the Big Data Steering Group and industry stakeholders meeting convened by EMA in May 2024. It was noted by EMA that the final publication of this work would be of interest and additionally would be relevant to the future RWD quality chapter planned for public consultation in 2024. This is the topic of this article.

We identified candidate frameworks and implementation tools through published and gray literature searches (material that generally would not be commercially published, e.g., regulatory and policy sites) (Figure 1). Among those identified, four frameworks and seven implementation tools were selected as having the greatest alignment, relevance, and capacity to the EMA DQF. This paper summarizes our findings and makes recommendations with the goal of inspiring further discussion and a common understanding across stakeholders of how to meet regulators’ expectations for data quality.

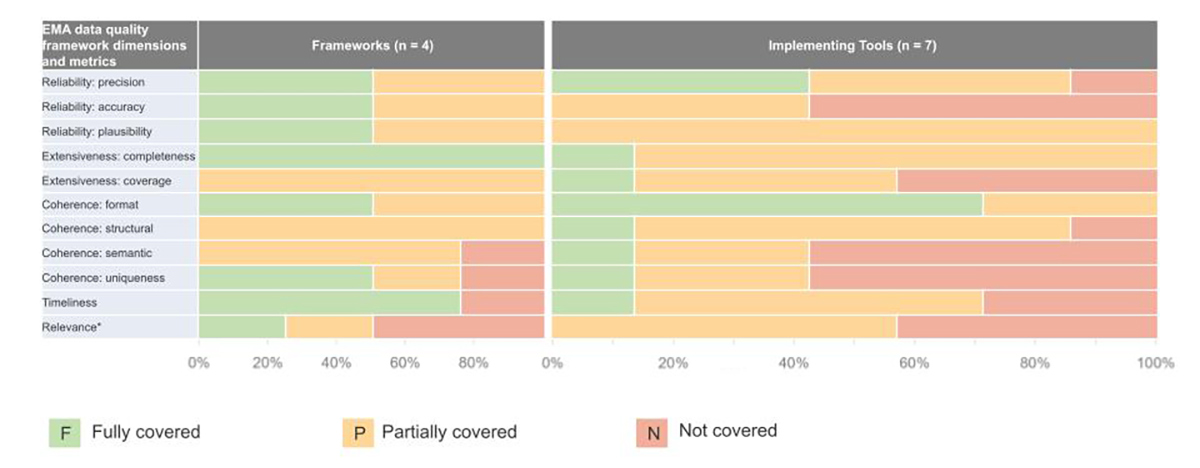

Full coverage (F) indicates that a tool conceptually covers an EMA DQF domain. Conversely, No coverage (N) indicates that the EMA DQF domain is not covered in a tool. Partial coverage (P) indicates that the tool has either an equivalent concept or requirement within the tool that allows aspects of an EMA DQF domain to be evaluated, but not to the full extent recommended. For example, tools that require the data dictionary and database schema to be provided to data users partially cover semantic coherence, given that the two documents allow a data user to understand which variables need to be tested for semantic coherence. However, without conducting analyses on these variables, it is not possible to fully determine semantic coherence. Assessments of alignment or completeness of implementation tools or frameworks compared with the EMA DQF can be subjective. While two reviewers independently conducted assessments and conferred/resolved any differences on each domain of each implementation tool or framework, ratings are subject to interpretation.

Note: X-axis represents the proportion of frameworks or implementation tools with each rating.

Framework References: Harmonized Data Quality Assessments (Kahn), Assuring Audit Readiness (TransCelerate), Data Utility Framework (UK HDR), Data quality criteria and indicators

Implementation Tool References: ATRAcTR, Facilitating Harmonized Data Quality Assessments, EUnetHTA REQuest, EMA REQueST, OHDSI tools (inclusive of Data Quality Dashboard and Data Diagnostics), DataSAT, SPIFD (Gatto)

Finding 1: No single existing DQ implementation tool addresses all aspects of EMA DQF domains

While many DQ implementation tools exist, some are more aligned with the EMA DQF dimensions than others; all have gaps that must be considered.

Frameworks referenced and reviewed as part of the EMA DQF and the EMA DQ workshop in 2022 (Analyses of Data Quality Frameworks for Medicines Regulation, April 2022) appear to have potential gaps for evaluating RWD quality. Additionally, a recent publication by Gordon, et al. also assessed open-source data profiling tools against UK Data Management Association (DAMA) data quality dimensions (completeness, validity, accuracy, consistency, uniqueness, and timeliness) which also reported gaps in assessing data quality. Both qualitative and quantitative assessments are necessary to establish data quality; thus multiple types of implementation tools may be needed to operationalize the DQF.

In our current evaluation, we found that the EMA DQF dimensions that were most commonly referenced in implementation tools included reliability: precision, reliability: plausibility, extensiveness: completeness, and coherence: format; however, the EMA DQF dimensions least frequently mentioned included accuracy, relevance, timeliness, coverage, and coherence: semantic, and coherence: uniqueness. Additionally, not all implementation tools or frameworks covered or defined the fit-for-purpose concept in the same way as the EMA DQF. Another identified inconsistency across implementation was the applicability of the specific tool to certain types of data (e.g., registries vs. electronic health records; primary vs. secondary data) including structure (e.g., common data model), and the research question intended to be answered by the underlying data (e.g., safety vs. effectiveness; descriptive vs. causal). There may also be varying utility of implementation tools depending on the data access structure, for example, with federated data.

Recommendation 1: Allow flexibility in DQ implementation tool selection

The existing implementation tools reviewed did not address all dimensions of EMA DQF and differed across data type and the research questions that the data are intended to address. As such, EFPIA considers that a specific DQ instrument should not be mandated by regulatory authorities. Instead, the instrument used should be selected at the discretion of the stakeholder responsible for its use, with its suitability justified on a case-by-case basis. This assessment should be undertaken on a risk-based and potentially iterative manner with different instruments used throughout the lifecycle of data use. Early dialogue and alignment with regulatory authorities on the selected tool(s) is warranted.

Finding 2: Differences in EMA DQF terminology and dimensions versus implementing tools

When identifying the utility of existing tools in implementing the EMA DQF for regulatory decision-making, the most commonly aligned terminology and dimension was Extensiveness: completeness (“measures the amount of information available with respect to the total information that could be available given the capture process and data format”). For other EMA DQF dimensions, it was unclear how these overlapped with terminology included in the other existing frameworks or implementing tools. For example, the EMA DQF “reliability: accuracy” dimension is defined as “The amount of discrepancy between data and reality.” In the Kahn framework (2016), for example, the closest concept is “Plausibility,” which “focuses on the believability or correctness of data and counts of data that conform to technical specifications (Conformance) and are present (Completeness) in the data.” Similarly, an implementation tool, ATRAcTR, defines accuracy of a data source “when it can be documented that it depicts the concepts they are intended to represent, insofar as can be assured by DQ checks (i.e., the data is of sufficient quality to investigate specific research questions)”, which is slightly different than the EMA DQF definition.

These few examples illustrate potential inconsistencies in terminology and dimensions to assess data quality that warrant attention.

Recommendation 2: Enable translation and mapping of EMA DQF elements to other frameworks to ensure synergy of DQ assessments and interpretability of DQ results requirements

To ensure the implementation of a robust DQ assessment for data sources used for regulatory research purposes, it is essential that DQ domains are transferrable among the existing DQ frameworks and implementation tools. Stakeholders should broadly map the EMA DQF definitions, domains, and dimensions to other existing DQ implementation tools to ensure synergy and efficiency of data collection and assessment for all data sources. This would enhance the interpretability of DQ assessments and reduce the burden for all stakeholders, particularly across regulatory authorities.

Finding 3: Data quality framework implementation is complex, iterative, and resource-intensive, requiring multistakeholder efforts, transparency, and an aligned understanding of data quality expectations

The process for implementing and documenting quality assessments requires an iterative process between data generators and end users, the latter of whom generally have limited or no control over how RWD is collected or generated and monitored for quality. Implementing tools require sufficient transparency and documentation for quality assessments. EFPIA member companies’ experience with implementation of DQ tools (e.g., REQuEST [EUnetHA or EMA versions]) is that while data partners generally have quality monitoring practices/standards, few have experience with reporting guidelines for payers and regulators.

Recommendation 3: Strengthen industry partnership with EMA and other stakeholders in the expectations regarding the implementation of EMA DQF

Given the complexity and potential impacts on resources for implementing the EMA DQF, it is critical for EMA to partner with industry and other stakeholders to ensure that expectations and responsibilities of the implementation of the principles and guidance outlined in the EMA DQF are clearly delineated. These include regulatory authorities, data holders, registry owners, HTA bodies, and registry holders, but this list is not exhaustive.

This will provide clarity on expectations regarding application of the DQF; ensure that assessments are feasible, focused on minimum standards, and easy to implement; as well as sufficiently derisk and optimize RWD use for regulatory purposes. Over time, these efforts will foster a real-world data ecosystem that incorporates quality by design.

Conclusion

EFPIA commends EMA’s effort to develop and adopt the DQF with the aim of improving DQ across the European Union and beyond. In order to make the DQ improvement a reality, there is a need to better understand EMA’s expectations about implementing the DQF in terms of process, stakeholders, as well as implementation tools.

DQ assessment is an iterative and complex process, impacting multiple stakeholders, thereby necessitating close collaboration to ensure clarity of expectations and enable the most efficient and robust approach in the implementation.

Given that no single existing DQ implementation tool or related framework was found to cover all aspects to be assessed in the EMA DQF, it is important to ensure flexibility in selecting tools with justifications by those responsible for generating the RWE. At the same time, various definitions and categorizations of the DQ assessment domains of existing frameworks should be synergized when we implement EMA DQF assessments to maximize the value of RWD evidence generation and quality assessment. Proactive effort and continued engagement are necessary for achieving alignment across all stakeholders.

Data Quality Framework: Key Findings and Recommendations

- No single existing DQ implementation tool covers all aspects of EMA DQF domains.

- Allow flexibility in DQ implementation tool selection.

- Differences in EMA DQF terminology and dimensions versus implementing tools.

- Enable translation and mapping of EMA DQF elements to other frameworks to ensure synergy of DQ assessments and interpretability of DQ results requirements.

- Data quality framework implementation is complex, iterative, and resource intensive, requiring multistakeholder efforts, transparency, and an aligned understanding of data quality expectations.

- Strengthen industry partnership with EMA and other stakeholders in the expectations regarding the implementation of EMA DQF.

Reliability: accuracy

Reliability: precision

Reliability: plausibility

Extensiveness: completeness

Extensiveness: coverage

Coherence: format

Coherence: structural (relational)

Coherence: uniqueness

Coherence: semantic

Timeliness

Relevance