Clinical Operations Specialized Consultant

WCG

Equipoise Consulting, LLC

DIA

Mural Health

linical trials play a crucial role in bringing new therapies to market. However, participation rates in many trials remain alarmingly low, particularly among underrepresented groups, despite numerous initiatives designed to address this challenge. A significant barrier is the financial burden placed on participants. The absence of sufficient financial support is overwhelmingly a factor that limits participation in clinical trials, especially those from lower-income backgrounds*.

Continued collaboration, innovation, and education will be essential to overcoming this challenge.

Today’s Approach to Participant Compensation

Currently, many pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies are making concerted efforts to create more fully developed internal guidelines for clinical trial participant payments. Even so, significant gaps remain in how participants are compensated. A recent analysis conducted by DIA examining US approaches—which included stakeholders across large pharmaceutical and smaller biotechnology companies—revealed that developed (or in development) guidelines are often inconsistent and lack standardization across the industry and therapeutic areas (TAs). The use of non-standardized terminology (for example, some sponsors use the term “compensation” while others use the terms “stipend” or “participant payment”) and varying compensation models complicate the implementation of reasonable and transparent payment systems. In addition, research institutions may have their own policies or practices regarding payment to participants that overlie and may contradict the practice a sponsor tries to implement across a study.

Reimbursement and Compensation Models

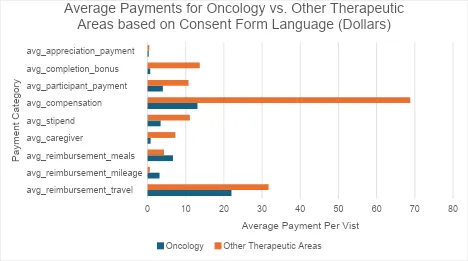

Participant payments typically fall into three categories: reimbursement for study-related expenses, compensation for time and effort, and incentive payments. Note that as used here, “reimbursement” does not necessarily mean the participant must pay initially and wait for repayment; it may include prospective payment of expenses incurred due to study participation. While there is consensus on reimbursing study-related expenses such as travel, lodging, and meals, the chart below illustrates that remuneration is still undervalued and not sufficient. In some cases, explicit expenses may be reimbursed, but more indirect expenses like childcare or other support needed to allow participants to devote the time to meet study commitments are not uniformly recognized. While it is encouraging that several companies seem to champion specialized approaches to providing caregiver payments for pediatric trials or rare diseases, it also raises the question: Are there other areas that would also benefit from these types of specialized approaches?

There is even less agreement on whether compensation for time and effort should be provided. For instance, some organizations use guidelines based on socioeconomic factors to determine payments, while others are developing internal policies. These internal champions are trying to consider more flexible approaches but are encountering internal challenges from a budget or compliance perspective. This inconsistency is particularly evident in oncology trials, where compensation for time and effort has seen slow uptake (see chart below for DIA Participant Compensation Analysis and Data provided by WCG). This may reflect long-held thinking in the clinical research world that in “therapeutic” trials, access to potentially beneficial study medication was sufficient “payment” for trial participation.

Related survey data from Mural Health proprietary research collected via 1:1 interviews by Mural Health’s Patient Kindness team, spanning many studies, further revealed the undervaluation of participant payments for oncology patients. A series of approximately 50 oncology patient interviews found that none of the interviewed patients had received any expense reimbursement and less than 10% received any form of a stipend. Mural Health attributed these results to a lack of regulation that enables basic economic principles of supply and demand: As the medical condition of an individual becomes more severe, their demand for experimental therapy becomes inelastic, which, consequently, allows study sponsors to reduce or eliminate the need to provide financial support to prospective participants. This trend is supported by data presented in “Reviewing Research Participant Payments Through a Diversity Lens” which shows that oncology indications, along with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, receive virtually no financial support.

In his effort to provide further evidence of this dynamic, Mural Health’s founder, Sam Whitaker, recounted a conversation he had with a senior clinical operations professional. When asked why the professional’s company did not provide financial support to American participants, she said, “We only provide [financial support] in countries that require it. All of our patients have cancer. They are dying. We don’t have to provide any payment. They will do whatever we want.”

Addressing Standard of Care (SOC) Coverage Disparities

A critical factor in reducing financial barriers and enhancing participant retention is addressing the disparities in standard of care (SOC) coverage. “Standard of care,” as used here, means any tests, procedures, or medications administered that would be performed or prescribed if the participant was receiving clinical care for the same condition outside the clinical trial.

Not all clinical trial participants have equal insurance coverage or the financial capacity to pay out-of-pocket costs such as copays, deductibles, and SOC procedures not covered by insurance. Research has shown that inconsistent SOC coverage can deter potential participants from joining trials and contribute to dropout rates. Further, a participant is not explicitly provided visibility into insurance coverage for SOC to proactively determine their potential expense outlay unless they attempt to collect this information prior to enrolling. Lastly, sponsor companies make no promise that the participant will receive the drug or that the drug will be effective.

Despite efforts for coverage of routine trial costs under the Affordable Care Act and the Clinical Treatment Act of 2022, the complexity of analyzing insurance coverage for SOC drugs and procedures in clinical trials inevitably leads to expenses for some participants. To mitigate these issues, some sponsors are exploring variable approaches to SOC coverage, such as developing cost-sharing pilots that consider participants’ income levels or providing direct financial assistance for SOC-related expenses. By implementing flexible and participant-centered policies, trial sponsors can create a more inclusive environment that recruits participants faster, reduces dropout rates, and ultimately enhances the diversity and success of clinical trials (DIA Participant Compensation Study).

Unfortunately, there appears to be a patchwork approach to paying for “fully loaded budgets” that include payments for SOC procedures, while cost-sharing exploration is in its infancy and not widely discussed due to legal complexities and risk concerns (such as anti-kickback violations, fraud, and abuse). This remains a complex arena in need of enhanced clarity and increased advocacy for more general regulatory guidance on permissible cost-sharing arrangements, as opposed to the burdensome requirement of getting separate Office of Inspector General (OIG) advisory council opinions for a cost-sharing waiver approval.

Ethical Considerations

As with most decisions in clinical research, establishing payments to participants must include consideration of the relevant ethical principles. The two most relevant of the three principles of research ethics described in the Belmont Report are respect for persons and justice.

Respect for persons requires that we treat each person as an autonomous agent able to make their own decisions about trial participation. The concern in offering them payment is that people will be persuaded to enroll in studies they don’t want to be in just for the financial benefit. This is a point worth considering, and one that ethicists have looked at carefully, especially in recent years, in alignment with the increasing role of patient advocacy and recognition of research participants as partners in research rather than just as research subjects. It is clear that conducting studies in a way that makes it easy and attractive for people to enroll—for example, by reducing unnecessary tests and providing convenient hours for study visits—are acceptable, effective inducements to participation.

Payment can also be considered an inducement. While inducements in themselves are not an ethical concern, there IS concern that “undue” payments will convince participants to take study risks they are not otherwise willing to take, and therefore payments that are “unduly high” (based on inconsistent and arbitrary standards) must be avoided. However, limiting payments that are “too high” effectively contradicts the principle of respect for persons because it assumes that the potential participant is incapable of weighing the study risks and benefits and making their own informed decision about participation.

In addition, if the trial has been approved by an institutional review board (IRB), an independent decision has been made that the risks of the study are reasonable in relation to the potential benefits. If these risks are reasonable when no payment is offered, they don’t become unreasonable when payment is offered. (Note: “Coercion,” defined as forcing someone to act by threatening them, is often referred to in payment discussions. Offers of payment are not threats, however; concerns about coercion are therefore not relevant to payment discussions.)

The principle of justice, sometimes described as distributive justice, demands that both the risks and the benefits of research participation are evenly distributed across populations such that no group of persons is disproportionally bearing the risks of research participation or reaping the benefits of clinical trials. If we refuse to pay research participants, the only people who will be able to participate in research will be those who can afford the time missed from work and the additional costs incurred as a research participant. This is not insignificant; one study found that participants in oncology trials reported an additional $200-$1,000 in their costs per month of trial participation.

If we only compensate participants minimal amounts for their time and effort, we may lower the barrier to participation of lower-income participants for whom participation becomes more feasible—but higher-income participants may feel that the minimal payments are not enough to outweigh the inconveniences for them, and the burden of research participation is then shifted to lower-income groups.

Financial Barriers are Limiting Socioeconomic Diversity

Financial barriers disproportionately affect lower-income participants*, who are more likely to decline participation due to out-of-pocket costs. This leads to a significant underrepresentation of these groups in clinical trials.

Research has shown that individuals with an income under $50,000 per year are more than 30% less likely to participate in cancer clinical trials compared to those with higher incomes. This disparity skews trial data and limits the generalizability of trial results, impacting the effectiveness of new therapies across diverse populations.

The American Association for Cancer Research Cancer Disparities Progress Report noted that based on analyses of clinical trial enrollment for gynecological cancers between 2004 and 2019, women living in small metropolitan counties were 30% less likely to participate in a clinical trial than women in larger counties.

Ongoing Efforts to Address Financial Barriers

DIA’s landscape analysis (download) highlights several ongoing efforts to address financial barriers in clinical trials. Key recommendations include developing standardized nomenclature and payment models, dispelling myths around undue inducement and IRB perspectives, increasing transparency in payment validation, gaining the endorsement of formal, senior organizational leadership, and including diverse stakeholder perspectives in policy development.

Some organizations are piloting innovative approaches: One provides for copays with strict financial criteria; another covers direct billing with ride-sharing companies and partnerships with nonprofits to manage participant payments. These efforts aim to help participants reach net financial neutrality, reduce the administrative burden on sites, and ensure timely and reasonable compensation. The industry needs to be more proactive in implementing these types of efforts across all therapeutic areas.

It’s worth noting that in August, Lazarex Cancer Foundation unfortunately ran out of funding for its Creating Access, Reimbursing Expenses (CARE) program, which provided clinical trial travel reimbursement and logistical support activities. After 18 years, it can attest to “providing reimbursements to over 12,000 cancer patients and caregivers” through a grant program to try to close the gap in health disparities. With the announcement of the end of their CARE program, Lazarex emphasized that the industry is still “routinely [falling] short of what patients need, [as] travel costs remain one of the top barriers to cancer clinical trials, leaving a staggering 93% of cancer patients without the help they need to participate.” (Statement by Dana Dornsife, Founder & Chief Mission & Strategy Officer, Lazarex Cancer Foundation). This shows how far industry still must go to truly reach the underserved, a systemic problem that industry must address head-on.

This issue goes beyond cancer patients. In one year, Harley and Maureen Jacobsen, an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patient and caregiver, incurred nearly $20,000 in expenses to participate in a trial but received only $2,000 in financial support.

It’s also worth asking why the goal of payment efforts should simply be financial neutrality rather than recognition of the time, effort, work, and inconvenience that participants experience to contribute their lives and bodies to the goals of research.

Enhancing Knowledge of Institutional Policies

Another silent yet known problem that surfaced throughout DIA’s analysis is that some institutional research policies may supersede a sponsor’s efforts to provide participant payments. A better understanding is needed of such policies, and there must be an open discussion on how to level-set and align such policies with sponsors’ efforts.

The Role of Policy and Legislation

Several policy proposals and legislative efforts are underway in the US to support these initiatives. For example, the Clinical Trial Modernization Act and the Harley Jacobsen Clinical Trial Participant Income Exemption Act aim to exempt certain payments from taxable income to help maintain social safety net assistance, thereby reducing the financial burden on participants. For lower-income participants, even small payments classified as income could risk disqualification from government subsidies such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Supplemental Security Income. If and when these bills become law, they will provide for a pathway in lessening the financial barriers that currently exist.

Additionally, organizations like the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have convened roundtable discussions to develop policy recommendations addressing financial barriers to trial participation. The Equitable Access to Clinical Trials (EACT) project recently released guidance for sponsors and sites, and the Toward a National Action Plan for Achieving Diversity in Clinical Trials report outlines collective goals and provides a specific call to action to the industry on actionable steps sponsors can take to reduce burdens and barriers to participation. DIA’s landscape analysis reflects similar findings, highlighting the gaps between and need for more industry cohesion around this topic.

DIA Recommendations for Industry Stakeholders

To reduce financial barriers and improve participant diversity and retention in clinical trials, industry stakeholders must adopt an approach that includes:

- Standardizing Participant Payments: Develop a common framework for participant payments with clear definitions and guidelines across therapeutic areas. Provide reimbursements and payments for time and effort to support the Belmont Report principle of respect for persons. The approach should involve collaboration with IRBs to ensure ethical compliance and avoid concerns about undue influence.

- Harmonizing Nomenclature and Processes: Standardize the language and the processes associated with participant payments to ensure consistency and transparency across the industry.

- Improving Transparency and Validation: Implement transparent and auditable systems for payment validation. Digital platforms that allow participants to manage receipts and track payments can reduce the administrative burden on trial sites.

- Incorporating Participant Feedback: Engage participants and patient advocacy groups early in the trial design process to better understand their financial needs and constraints. This should begin as early as the feasibility phase to tailor compensation models effectively.

- Enhancing Education and Awareness: Provide education and training for study teams, sponsors, and IRB members on ethical considerations and best practices for participant compensation to dispel myths about undue influence and highlight the importance of reasonable compensation.

- Advocating for Policy Change: Support legislative initiatives aimed at reducing financial barriers, such as tax exemptions for participant payments. Engage with policymakers to ensure that these initiatives meet the needs of the clinical research community.

- Securing Executive-Level Commitment from Sponsor Companies: Create an up-to-date internal formal policy or guidance and gain buy-in from the highest levels of the organization. This includes fostering an understanding of the challenges, aligning budgets accordingly, and providing education and impact training to help decision-makers understand how their policies and procedures affect patient outcomes. This can enhance patient satisfaction and increase trial diversity, and it may improve return on investment (ROI) by accelerating enrollment and reducing dropout rates.

Conclusion

Addressing financial barriers to clinical trial participation is critical to enhancing diversity, improving retention rates, and ensuring trial success. By adopting standardized, transparent, participant-centric payment models across TAs, industry stakeholders can create a more inclusive environment that benefits participants and the broader medical community. The DIA Consortium and other industry leaders offer a promising path forward, but (as stated above) continued collaboration, innovation, and education are essential to achieving these goals.

* See White Paper: Compensating Participants in Clinical Research: Current Thinking, ©WIRB-Copernicus Group 2017. Other references are available upon request.

Funding to support DIA’s Landscape Analysis was graciously provided by Greenphire, Mural Health, Myonex, and WCG.

Other contributors: Bain & Company, AS Pharma Advisors, the Society for Clinical Research Sites (SCRS), and The Beautiful Way.