here are few things that a parent dreads more than having a sick child. But the journey to diagnosis and recovery for what could be a child’s fatal illness can be even more difficult.

When her 8-year-old daughter Autumn was diagnosed with Stage 2 T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), Ebony Dashiell-Aje knew that their family was about to venture down a challenging road. But she didn’t anticipate how Autumn’s outlook would help lead their family through their darkest days, or help encourage others through a documentary of their experience titled Autumn’s Story.

In the following interview, Ebony shares three perspectives on Autumn’s road to diagnosis, treatment regimen, and recovery: as a pharmaceutical industry professional leading patient-centered outcomes research, as a pediatric oncology patient caregiver, and as Autumn’s mom. The video documentary and our audio interview with Autumn are embedded within this interview.

Ebony Dashiell-Aje: In Autumn’s immediate household, it’s myself, my husband, her younger sister who turned 8 in November, and her younger brother who turned 5 in June.

DIA: How old was Autumn when she got sick?

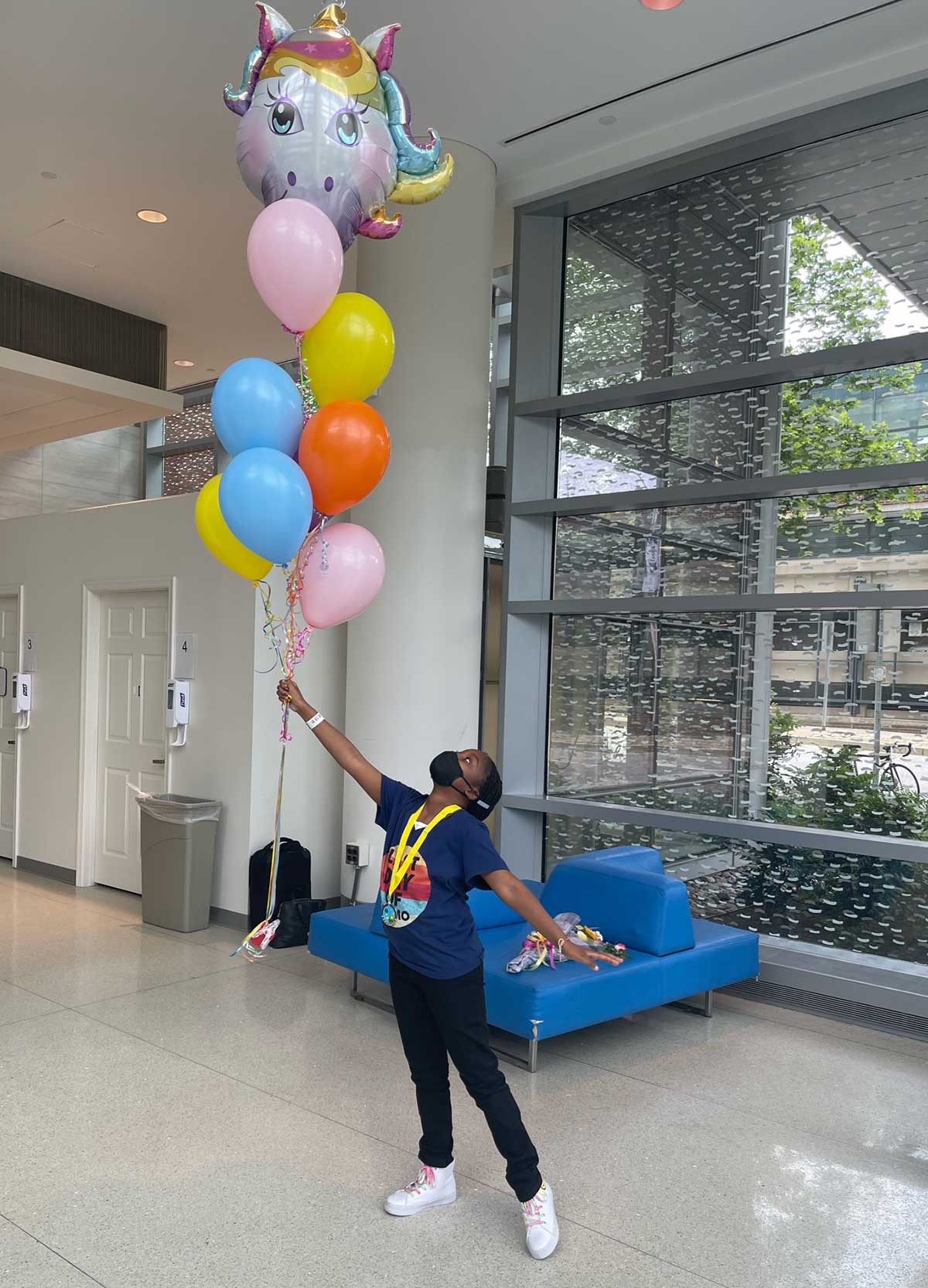

E D-A: She was 8 when she was diagnosed, in 2020. She underwent two and a half years of treatment, and her last chemotherapy treatment was in June 2022.

DIA: Can you describe how you came to learn she was sick?

E D-A: In December 2019, she came to me one night before bedtime and was very worried. She asked, “Mom, does my neck look swollen?” I looked at her left side and her lymph node was very swollen and I knew this wasn’t normal. I touched her neck and asked, “Baby, does this hurt?” She said no. At that moment, my heart sank; I knew that if it didn’t hurt, it could possibly be cancer.

I’m not a clinician, but at that time I was working at FDA, surrounded by clinicians. Every day, I heard about rare diseases and patient experiences, including experiences with cancer (that cancer often didn’t hurt). When she said it did not hurt despite it being swollen, that worried me.

DIA: What was it like being in Autumn’s story as her mom but then also realizing from your professional perspective what she was stepping into?

E D-A: As her caregiver, I was worried about an acute emergent symptom that popped up literally out of nowhere. She went to school that day and nobody saw anything; she came back home at night, and there was this lump on her neck.

My husband and I shared this discovery with our parents right away. Since my mother was a caretaker to my ailing grandmother, I’ve seen what disease and illness can do, and believe I’ve been equipped with skills to handle these circumstances. But I can say, it was God’s gift of peace and promise which helped me know that regardless of what this was, we were going to get through it.

From a professional perspective, I knew the road could be long to both diagnosis and recovery. I was bracing myself for the possibilities and for the worst.

DIA: What was your experience in getting Autumn diagnosed?

E D-A: The road to a diagnosis wasn’t easy. At the time we scheduled her first doctor’s appointment, RSV and flu were overtaking the healthcare system and appointments were scarce. Once we got an appointment, her doctor was taking a very conservative “wait and see” approach, beginning with a physical examination and full blood workup to figure out the source of the issue. They were very thorough and asked all the questions: Has she been exposed to anybody with HIV? Has she been exposed to anyone who’s recently been out of the country? Trying to rule out all the communicable diseases that could cause some lymphatic system response. As a precaution, she was also put on antibiotics in case she had a bacterial infection, and we were scheduled for a follow-up visit.

At that follow-up visit, we were told that her blood work came back normal. However, the lump on her neck had grown—still with no pain—despite the antibiotic. The doctor noted that kids have reactive lymph nodes, which can take up to six weeks to resolve, all the time. He also explained that he wanted to expand the blood work panel to include additional things—and, he whispered to me, he wanted to rule out malignancy.

Once the second panel results were in, the doctor called to tell us that all her levels were normal and there was no sign of malignancy. We were to see him after Christmas if things hadn’t improved.

Well, things did not improve. They only got worse. To be honest, as her caregiver, I felt shuffled around. But this increased our sense of urgency to get answers more quickly.

DIA: How was Autumn holding up through all this uncertainty?

E D-A: You could tell it was pushing her, but her personality has always been very carefree, very bubbly, and she was still our sweet Autumn. But in just two weeks, both sides of Autumn’s neck began to swell until she looked like she had a neck full of lumps. We wondered if Autumn was thinking about how she looked, or concerned that we didn’t have any answers yet, or wondering if this was going to be permanent for her.

DIA: How were you holding up?

E D-A: As a caregiver, there was this delicate balance of having this child who doesn’t quite know what’s going on, trying to protect her innocence and emotions, and yet not misleading her.

I was trying to embrace and protect my child and then also advocate, making sure that she was getting the proper care. I knew that I was privileged, because I could reach out with questions to a wealth of professional connections. I told my friends. I sent pictures to clinicians. We have a neighbor who is an ER (emergency room) nurse that was critical in changing the course of her care: He came over, examined her, and recommended we ask the doctor to order a CT scan so we could get answers quickly.

DIA: Did you follow that advice?

E D-A: Yes, I did. I called the doctor’s office and told them I was advised to ask for a CT scan.

By that time, the doctor’s office was even more overwhelmed with flu and RSV patients, and so they didn’t have time to speak with me right away. Even when the nurse called back, she informed me that the doctor wouldn’t order a CT scan. I eventually spoke with the doctor, who explained why they would not order it: They liked to be conservative and not expose pediatric patients to the risk of unnecessary radiation.

I understood their perspective but was still quite upset. I was very much aware of the benefit-risk balance, as a regulator at FDA. But it felt they were taking away our family’s choice. The doctor made the executive decision, despite the small risk of one CT scan and despite the second opinion we received.

At that point, my husband and I decided that if this continued to progress, we were taking Autumn to the ER.

DIA: Did you end up having to visit the ER?

E D-A: Yes. We got through the holidays, and it didn’t get better, so we went to Howard County General Hospital on New Year’s Eve. They performed the physical examination and CT scan, which indicated that both her right and left cervical nodes and her interstitial lymph nodes were involved. The lymph node swelling had spread down to her chest.

After waiting for hours, the doctor confirmed to me that her blood work indicated positive markers of malignancy. We were then referred to the Johns Hopkins pediatric oncology unit.

DIA: How was Autumn told about, and how did she respond to, her diagnosis?

E D-A: After the ER doctor told us she was sending us to Hopkins, Autumn asked, “So what did they find?” I said, “They still have to do a few more tests to determine exactly what it is (which was true), and we have to go to another doctor later in the week.” I didn’t want to mention cancer to her.

After we went to Hopkins, we explained that this could be a number of things, but they thought it could be one type of thing—that this could potentially be a specific type of cancer. That was the first time she heard the word “cancer.” Then the doctors told her that the final diagnosis would determine the course of treatment: If it was lymphoma, there’s one treatment course; if it was leukemia, there was another. They explained to her how they had to figure out what it was but also how far along it was.

They determined that Autumn had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, T-cell type. She had the trickier type, which meant that she needed extra direct treatment into her central nervous system. Some of the drugs were stronger and she had to have more spinal taps throughout her treatment course.

The doctors did a great job explaining things in simple terms to Autumn and delicately explaining that the process was going to be long and arduous.

DIA: Her spirits remained relatively unchanged?

E D-A: Yes, she was still acting the same. We let her go back to school for one day after winter break before we went to Hopkins. We asked her afterwards how she felt about her school year, and she replied: “I think this school year is going to be great. I have a feeling that God is going to reveal more of Himself to me.” Little did she know what was really going on.

DIA: Was that one day of normalcy good for her?

E D-A: Yes, her friends hadn’t seen her since before break. She looked more deformed than before, and we were concerned about how she felt about herself. We tried to undergird her before she went into school in case she got looks or comments. The biggest blow was to tell her that she would have to be remotely schooled after that day. That was hard for her to process, but she took it in stride.

Her school made sure to help provide normalcy throughout the journey too. They sent food. Her peers sent her gifts and videos to encourage her. Autumn was able to video conference into class and moved around her school using an iPad on a pole. They had designated Autumn chaperones who carried her pole around the school, up and down steps, from class to class. It was amazing.

DIA: After that normalcy, were there any other surprises?

E D-A: Doctors did not give us all the information about the treatment cycles and challenges at first, which is understandable. They try to give it to you in stages, to make it less threatening from the very beginning.

Another thing we didn’t understand was how many medications she would be on at once. It wasn’t just one treatment. At one given time, she was on 11 medications, and, of those, five chemotherapies delivered through different modalities. There was intravenous administration, oral, and then the intrathecal spinal tap once a month. Then she had to get a cocktail of different chemotherapy drugs, oral plus intravenous administration; I was even trained and administered subcutaneous chemotherapy to Autumn at home during the pandemic. Not to mention a slew of medications to manage the side effects of the chemotherapy. It was overwhelming at first.

DIA: Could you see any signs that the treatment was working?

E D-A: After her first treatment, her lymph node swelling went down immediately. However, after that, we soon realized that one sign the medication was working was when Autumn looked and felt her worst. That was the hardest part. She looked very sick. At the very end, she started to look a little better. But the process was not pretty.

DIA: There’s a brightness to her voice. You always saw and heard that light?

E D-A: We always saw the light and encouraged her to see it, too. One thing we realized as caregivers: You have to be there for your loved one. You have to be their strength at times when things are uncertain. She really did rely on us and our strength to carry her through. We didn’t realize how much that meant until she reflected at the end. That meant a lot to us because when you’re going through it as a parent, it’s hard to be that rock.

DIA: Did you perhaps know too much, as a scientist, about what Autumn was going through?

E D-A: At times, I’d have to keep myself from thinking of the “what ifs” but overall, the knowledge, coupled with hope and faith, helped. There’s tons of literature, including a recent review in JAMA, pointing to positive associations between faith and quality-of-life outcomes among patients and their families. Being able to hold onto that hope is sometimes the difference. I think that has been the key for Autumn, too: She knew that she was secure, so that when things were going haywire, she was able to hold on.

DIA: But there’s a glorious day coming. You’ve shared your perspective as a caregiver and an industry professional, but take us through that conversation as Autumn’s mom.

E D-A: It was very surreal, and it wasn’t without hiccups. Autumn’s body was very sensitive to chemo, which meant that the chemo worked a little bit too well at times, and there was a period when she was a poor metabolizer. They had to keep very close watch on whether the drug was working or not; it took some time to get her to the right therapeutic level because her system did not metabolize the drug. That was one of the toughest periods. It was devastating to entertain the thought that after we’d gotten so far, it was possible that the only treatment regimen proven to treat her illness effectively may not work for her in the long run…

But then the glorious news did arrive! We’re thankful for God and for Autumn’s care team and for the important research that made another medication available to help Autumn metabolize her chemotherapy, and her body responded well.

DIA: How is Autumn as of November 2023?

E D-A: She is a tween. She’s turned 12, and you would think that nothing ever happened to her. She’s active. She’s very much still a great student. Psychologically, I think she’s fine.

But there is a chapter of continuous monitoring for five years after her last treatment. She still has to go to the clinic and at times I think it reminds her. But she’s still taking things in stride. Now we have to try to build up her muscles and immune system. She has to take supplements and vitamins to help with her bone health. She’d rather not deal with that type of stuff, but we are grateful she’s still with us.

DIA: What is the name of the documentary and how did it come about?

E D-A: My husband had a coworker who did a documentary about his father. This idea kept coming up throughout this process, so we originally decided to document it just for us, personally. But through the process, the filmmaker helped us to think it may not be just for us: We should share Autumn’s testimony of hope and strength for others to see. We premiered it at a gala last summer and also incorporated a fundraiser for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society to give back. We have since done a web release. The title is Autumn’s Story and it’s on YouTube.

DIA: Was there a point where you felt proud not only of Autumn and your family but of your profession?

E D-A: I felt proudest about being an advocate for my daughter. In that process, I was advocating not only for my child but for generations of children and families.

People at Hopkins told me that we educated them on how best to be patient-centered because I shared my knowledge. My entire career is built on patient-focused drug development. What better way to take the caregiver’s “exam of a lifetime”? It was a trial by fire, boots to the ground, learning experience—a true application of patient-centricity. If God ever sent me on a mission, this was it.

DIA: Can you see the day when we just say “drug development” because the “patient-focused” part is implicit and understood?

E D-A: People think about “patient-focused” when companies develop drugs. But the care management that happens after must also be patient-focused. That’s the full circle: It’s not just developing the drug. It’s not just putting it on the market. It’s not just getting someone to put it in their body. How do you treat a patient and their families with dignity during the treatment course? That piece isn’t figured out all the way and it’s variable across clinician-patient relationships. We’ve come a long way being “patient-focused,” but there’s still work to be done.

DIA: And how can it be quantified in a business that is so based on data?

E D-A: That’s where advocacy comes in: Expressing the value of hearing the patients and (like Autumn said) believing a patient when they tell you it’s not working, or that they want something new, or that they’re willing to take the risk. Listen to patients when they tell you: “I understand that, but this is who I am. Don’t just put me into the box with that case study report from JAMA.”

I’ve been empowered as a professional to be unashamed. This is my life. This is what we went through. Put yourself in your patient’s shoes: How would you design this study so that they would want to participate, or ask them to fill out this questionnaire because it is meaningful to them? How would you best handle someone with care when they face difficult odds? Adding this perspective will help us all elevate the value of patient-centricity in medical product development and clinical care.

Listen to Autumn’s interview below.