Around the Globe

Nippon Medical School

atients with COVID-19 in Japan were first identified in February 2020. This was only the first wave. A state of emergency was issued, and a lockdown of major cities was implemented from April 7 to May 25. Gradually, the second wave was confirmed in the summer of 2020. The third wave occurred around October 2020, and the state of emergency was reissued on January 7, 2021.

These important developments and consequent actions taken in response were overviewed by IFAPP, IFAPP Academy, and JAPhMed in the webinar COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan: Facts and Expectations sponsored by DIA Japan and reviewed below.

Organization and Communications

In terms of morbidity, Japan is similar to South Korea and Indonesia in death cases per one million population, at a rate only 5% that of the US.

COVID-19 Treatments and Vaccines in Japan

According to the Guidance for Medical Practice for COVID-19 (Ver 4.1), Japan has two recommended treatments for COVID-19: remdesivir (RNA synthetic enzyme inhibitor) and dexamethasone (steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, SAD). As of February 2021, Japan has 14 medical devices and 43 in vitro tests for COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment. The Chief Executive of Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) has issued nine statements titled PMDA’s Efforts to Combat COVID-19 during the pandemic.

“Zero-based thinking,” or “thinking outside the box,” was deemed to be another key success factor in the rapid development of COVID-19 treatments and vaccines. It is important to have a high tolerance for uncertainty when tackling unprecedented challenges. For example, the relevant parties should collaborate to generate new social-beneficial innovative values across and beyond the boundaries established between academia, industry, and health authorities. In our current, highly uncertain circumstances, attitudes toward uncertainty are critical. Perceptions of acceptable and unacceptable risk have been changed by these unprecedented challenges, which may open the door for a “new normal,” both in Japan and globally, in the future.

Remote Audits of Clinical Studies in Japan During the Pandemic

In 2020, a survey questionnaire was sent to 18 pharmaceutical companies, 14 CRO companies, and 97 medical institutions to investigate issues at sponsors and medical institutions during GCP audits. The sponsor side expressed 100% interest in improving the audit environment for medical institutions, while the medical institution side expressed only 43% interest. We can confidently say, under the current COVID-19 infection situation, that it is an urgent task for medical institutions to promote understanding of audits and to practice remote auditing and monitoring.

The survey examined benefits expected from the introduction of remote auditing in cost, delivery (time), travel-related risk, and flexibility through an additional questionnaire sent to 13 audit sponsors. All audit sponsors except for one answered that by conducting remote audits they could save at least 500,000 Japanese yen (USD $4,776) a year, and eight of those expected to save more than one million Japanese yen (USD $9,552) a year. Outside Japan, 6 out of 13 audit sponsors expected savings of at least two million Japanese yen (USD $19,104) annually.

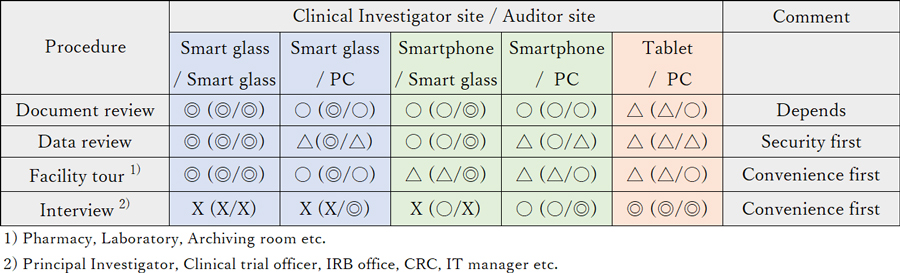

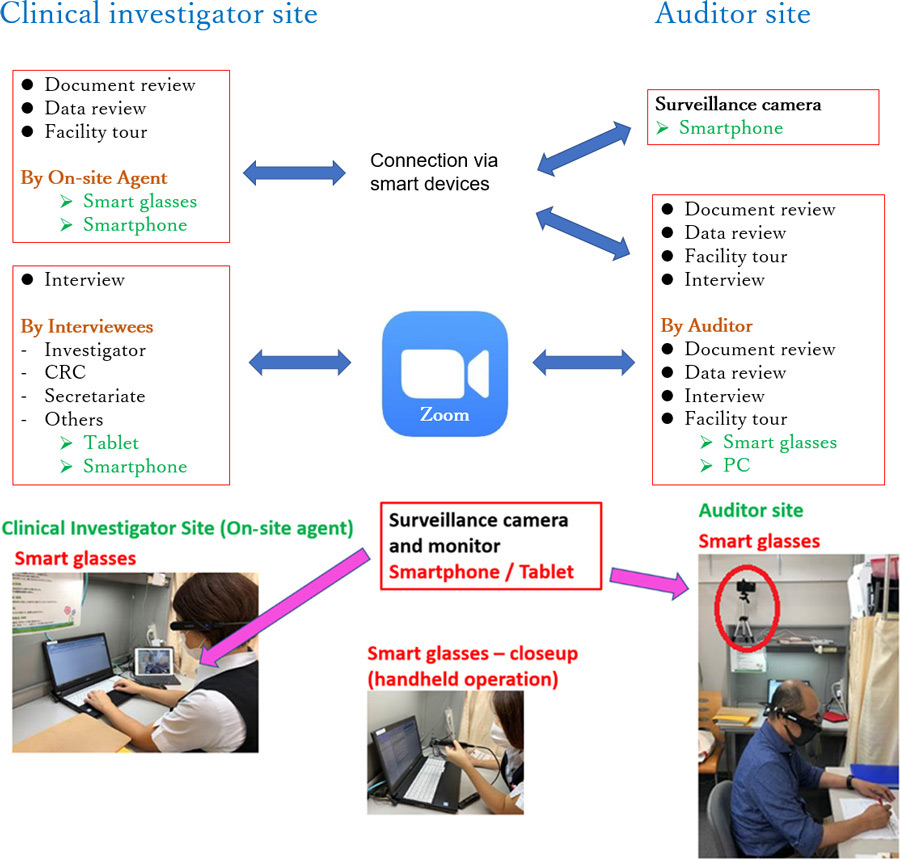

To assess the feasibility and usefulness of remote auditing, an observational study was conducted at hospitals that accepted remote audits, and one research group including members of the University of Tokyo and Nippon Medical School assessed these elements in a series of verification experiments using Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools. As shown in the audit plans (Figure 1), verification experiments of remote auditing were conducted at two clinical investigator sites using a combination of smart glass, smartphone, and tablet (Figure 2).

The clinical investigator site and the auditor site were connected online, and audit procedures were executed without visiting the site. An on-site agent was assigned and trained by the audit sponsor to show trial-related documents and data to the ICT tools to avoid disruption in the daily operations of trial staff at the site. A surveillance camera was used at the audited site to monitor the auditor’s every move, demonstrating the importance of information security management by enabling the clinical investigator site to constantly watch the auditor.

- Principal Investigator oversight

- Informed consent process

- Source data verification

- IRB approvals and communications

- Investigational product handling

- Safety reporting

- Investigator Site File

- Monitoring and Facility

- Principal Investigator oversight

- Informed consent process

- Source data verification

- IRB approvals and communications

- Investigational product handling

- Safety reporting

- Investigator Site File

- Monitoring and Facility

The data-review audit process must emphasize security first. On the other hand, convenience for both facility inspections and clinical investigator interviews is also of great value. We evaluated the usefulness of each ICT tool with respect for each activity.

Other Discussions

The International Federation of Associations of Pharmaceutical Physicians and Pharmaceutical Medicine (IFAPP) was established in 1975. The mission of IFAPP is to promote Pharmaceutical Medicine by enhancing the knowledge, expertise, and skills of pharmaceutical physicians and other professionals.

The Japanese Association of Pharmaceutical Medicine (JAPhMed), a national member association of IFAPP, has more than 50 years of history in developing pharmaceutical medicine in Japan and has over 200 members, mainly from the pharmaceutical industries.

The author also serves as Director and Board-Certified Member of JAPhMed, and as Secretary, IFAPP.