Putting Recommendations for Plain Language Summaries into Practice

@EnvisionPharma

lain language summaries (PLS) of publications form part of the wider democratization of science, enabling a broader audience to access and potentially understand scientific and healthcare research. However, many practical questions around these important summaries remain: what types of PLS should we be writing, which publications should have a PLS, and where should PLS be published? Three key sets of recommendations for PLS were released in 2021. This article explores what these recommendations mean in a practical sense and what more is required to further the development of PLS in terms of support and guidance.

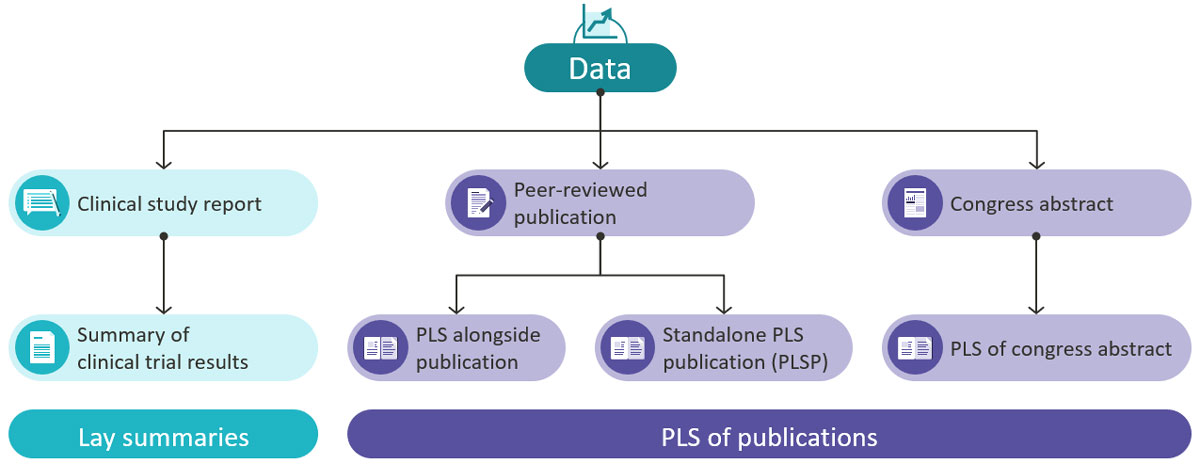

A plain language summary (PLS) is a short summary that presents medical research in a clear and understandable way without jargon. PLS of publications are based on peer-reviewed medical journal articles and congress presentations. These summaries are distinct from regulatory clinical trial results lay summaries, which are mandatory in the European Union as part of the Clinical Trial Regulation EU No. 536/2014 and aim to return results to study participants.

PLS of publications come in a wide range of formats and lengths, ranging from short text-only PLS, which are similar in length to the scientific abstract, to longer PLS incorporating visuals. PLS often form part of the scientific article or are published alongside it–for example, in supplemental materials as well as separate repositories such as Figshare. PLS can also be developed as standalone publications (known as PLS publications, or PLSP). These are acceptable secondary publications and have their own unique identifier (DOI).

PLS are accessible to a broad audience, including nonspecialist healthcare professionals, patients, and the public. Research is starting to define our understanding of the value of PLS and how they are being used. For instance, PLS can improve lay audiences’ understanding of research results, are being used by healthcare professionals with their patients, and can lead to an increased number of views of the original scientific article.

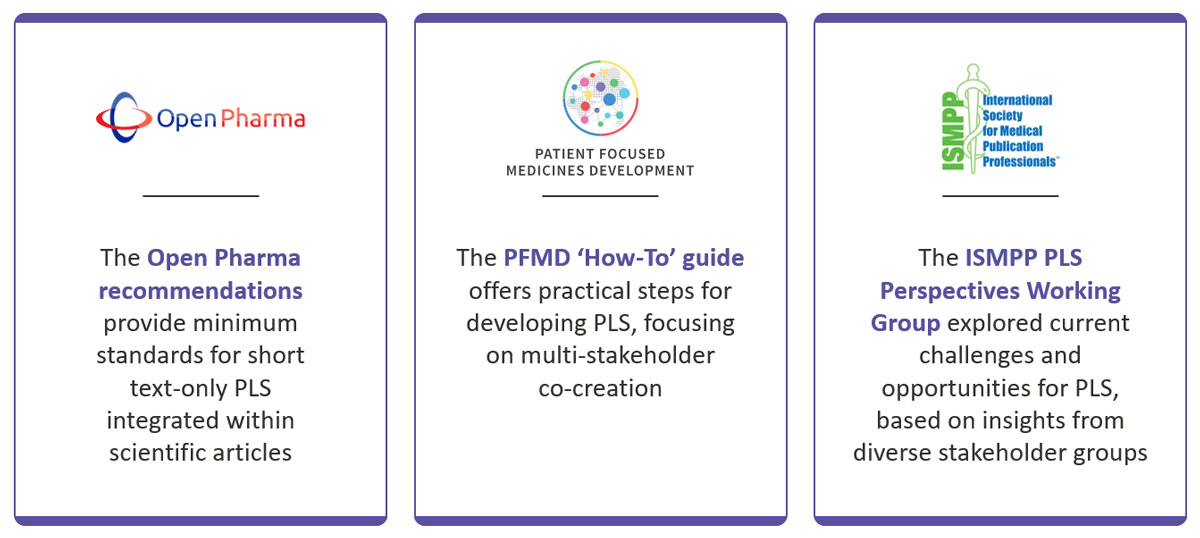

PLS are increasingly being embraced by journal publishers and study sponsors. Alongside this growing interest, recommendations have been developed to help inform best practices. Three key sets of recommendations for PLS of publications were released in 2021.

These recommendations inform PLS best practice in different ways. The minimum standards for short text-only PLS, as proposed in the Open Pharma recommendations, aim to “build a universal foundation that encourages the accessibility, discoverability and inclusivity of PLS.” Short text-only PLS can be indexed in PubMed. This could make it easier for readers to access them, as there is no pay wall and they do not have to read the scientific article to find the PLS. Discussions are ongoing around whether certain audiences such as patients use PubMed, and the role other platforms such as Figshare, which links to Google Scholar, have to play in hosting PLS. In addition, effective plain-language communication can be enhanced by visuals, infographics, and digital enhancements, which the authors acknowledge fall outside the scope of this guidance. The Open Pharma recommendations focus on PLS of company-sponsored medical research, and pharmaceutical companies are coming on board with this. For example, Ipsen announced at the recent virtual ISMPP EU meeting (25–26 January 2022) that they will be developing text-only PLS for all company-sponsored journal publications covering human studies from July 2022.

The Patient Focused Medicines Development (PFMD) how-to guide for PLS of publications has a broader focus. It was developed by a multidisciplinary working group of patients, pharmaceutical companies, publishers, and publications professionals, and is intended for anyone who needs to write or contribute to a PLS, including patients and caregivers, patient organizations, pharmaceutical companies, and healthcare professionals. The guide provides a practical seven-step approach for PLS development, from setting the rationale and scope for the PLS through to tracking dissemination and measuring success. It proposes ethical standards for PLS, such as the need to align the content of the PLS with the original scientific article and using neutral, nonpromotional language. The guide also has a strong focus on cocreation, giving details of how patients and other audiences can be involved in PLS development, and considerations for patient involvement at each step based on the PFMD Patient Engagement Quality Guidance.

Rather than giving specific recommendations, the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) PLS perspectives publication provides an evidence base to help inform future guidance on PLS. The authors used a modified Delphi process to gather feedback from diverse stakeholders (pharmaceutical companies, publishers, medical communications professionals, patient experts, healthcare professionals, and media) to prioritize the key questions that need to be considered to improve PLS uptake and quality. This publication covers some of the same considerations as the PFMD how-to guide, such as target audiences for PLS, key information that PLS should include, and PLS metrics. It also provides context for where the short text-only PLS recommended by Open Pharma are the most suitable format, for example, where the primary consideration is translation into other languages or budget constraints. The insights gathered focus on PLS of company-sponsored medical research, so the ISMPP PLS publication may be particularly relevant to companies that are exploring PLS or refining their PLS process. For instance, it includes an example PLS development process and potential criteria for selecting which publications should include a PLS. However, the authors acknowledge that many of the insights will be relevant for PLS of research funded by other means.

The industry is rapidly moving ahead with PLS, and more definitive guidance is needed. In a poll taken of attendees at a recent ISMPP U webinar (2 February 2022), 89% of respondents stated that they were already on board with PLS or were ready to start adopting PLS. There is momentum to address unanswered questions around PLS, as evidenced by the high interest in PLS as a research topic at the ISMPP EU 2022 meeting. For example:

- What is the value of PLS to different audiences?

- Where and how should PLS be published to ensure optimal reach and discoverability?

- How can the reach, value, and quality of PLS be measured?

- How can PLS meet the needs of non-English-speaking audiences and account for different cultures?

Although there is no one-size-fits-all approach to PLS, industry-wide guidance is needed to drive widespread uptake, standardized quality, and consistent dissemination of PLS. “The role of, and information for, the patient” has been announced as the top priority topic that will be addressed by the updated Good Publication Practice (GPP4) guidelines, due for release in early May 2022. GPP4 will also provide guidance on social media usage, which may help to guide unanswered questions about how companies can share PLS to widen dissemination. This guidance should help to move PLS forward as one small but significant element in the wider democratization of science.

Plain language summaries (PLS) of publications: Focus on practical applications. ISMPP U Webinar